In August 2019, the Business Roundtable came out with a new statement on the purpose of a corporation. For the first time, the focus expanded from serving shareholders and creating long-term value to serving all stakeholders by delivering value to customers, investing in employees, dealing fairly and ethically with suppliers and supporting the environment and people in the community.

While this statement is bold, it is a response to the increased focus by shareholders on Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) matters. Investors are evaluating how companies are addressing ESG issues and their impact on the long-term sustainability and value creation for each organization. Some of the largest institutional investors, including BlackRock and State Street, have put boards on notice that they will be holding directors and company management accountable for how ESG issues are managed. The major proxy advisory firms (Institutional Shareholder Services and Glass Lewis) now provide their clients with ESG ratings for each company they evaluate, highlighting related risks to investors in these areas.

What should board members generally and compensation committee members specifically be doing to address ESG? Each board should define what ESG means for their organization as each company has a unique operating model or business strategy that may include ESG initiatives to varying degrees. Many boards are doing this. We have seen the creation of ESG committees of the board or modifications to committee charters to incorporate ESG oversight (for example, many compensation committees now have oversight of diversity and inclusion). Once companies and boards define what ESG means for them, it will be important to articulate the following:

- Objectives for each of these initiatives

- Criteria for assessing performance against these

objectives - Approaches for holding management accountable

The governance area of ESG has improved in the past decade, with many organizations focused on strengthening shareholder rights and demonstrating the alignment of pay and performance in response to input from shareholders and shareholder advisory

groups. A strong and independent board is a key factor in governance and across industries, and many boards have embraced independent director sessions, board refreshment and balanced tenure, skills and diversity. Showcasing of governance enhancements has become common in proxy statements, and we expect companies to continue to maintain strong governance practices.

The environmental aspects of ESG have been more common in certain industries, such as energy, utilities and manufacturing, though the focus on the environment is gaining momentum across industries.

Companies are focusing on how they manage climate change, emissions, spills, water conservation and other sustainability efforts. Organizations such as the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board have developed standards so companies and investors can assess the risks and opportunities across industries.

The social aspects of ESG have focused on human capital and the impact of a company’s products or policies on society. The topics of human-capital management, employee engagement and gender pay equity have increasingly worked their way into board meeting conversations, with gender pay equity raising the fundamental issue of representation and inclusion. These statistics are measurable, and detailed analysis over time can help hold management accountable and demonstrate progress. It is now very common for compensation committees and, in some instances, the full board to receive updates on representation across an organization.

A natural question is to what extent should ESG factors be incorporated into incentive compensation plans? CAP reviewed the proxy statements of 2020 early filers (companies that filed their most recent proxy statement between December 2019 and January 2020) and found that approximately one-third incorporate some type of ESG metric in their executive compensation plan decision-making. The types of metrics varied significantly by industry as not all aspects of ESG will be critical to every organization’s business strategy. For example, carbon emissions may be more material for an energy company than a professional services company. When incorporating ESG factors, most companies in our review applied the metric to their annual incentive plans using a qualitative assessment of the factor. The metric generally reflected a small percentage of the overall weighting (5 percent–15 percent of the total incentive). Companies and boards should discuss the best ways to hold management accountable for ESG progress, including incorporating such progress into incentive plan performance.

Every board and management team should identify which ESG matters are material to their organization and understand how they should be approached and monitored and how to communicate their approach to investors. While the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020 has turned the focus of management on business continuity and crisis management, we expect ESG matters will continue to be prominent factors considered by institutional investors, proxy advisory firms and other stakeholders. It will be important for companies to define the ESG factors that have the greatest impact on their business as transparency and disclosure on how ESG matters are addressed have become increasingly essential parts of shareholder engagement.

The CAP 120 Company Research consists of companies from ten industries, selected to provide a broad representation of market practice among large U.S. public companies. In this report, CAP reviewed Pay Strategies, Annual Incentives, Long-Term Incentives, Perquisites, and Stock Ownership Guideline Requirement Provisions of these companies in order to gauge general market practices and trends.

Characteristics of the CAP 120 Company Research Sample

The CAP 120 Research Study consists of companies selected from ten industries intended to provide a broad representation of market practice among large U.S. public companies. The fiscal year revenues of the companies in our sample range from approximately $3 billion to $500 billion (median revenue of $32.7B) and are summarized in the following exhibits.

| Financial Summary ($M) | Cumulative Total Shareholder Return Ending on 12/31/2018 | ||||||

| Percentile | Revenue | Net Income | Assets | Market Cap | 1-Year | 3-Year | 5-Year |

| 75th | $67,103 | $6,804 | $172,979 | $99,181 | 4% | 50% | 73% |

| Median | $32,716 | $3,183 | $61,495 | $43,956 | -12% | 21% | 33% |

| 25th | $18,762 | $1,654 | $25,487 | $21,535 | -23% | -4% | 1% |

Pay Strategy

Among companies in CAP’s 120 Research, 97% disclose using a peer group for pay benchmarking purposes. The median number of companies in a peer group is 18.

Consistent with last year, approximately one-third (31%) of the companies with a peer group use more than one peer group. Companies with multiple peer groups either use two peer groups for pay benchmarking (e.g., an industry specific peer group and a general industry peer group) or use one peer group for pay benchmarking and another peer group for relative performance comparisons.

| Peer Group (n = 116) | ||

| % of companies with a disclosed peer group | % of companies with more than one peer group (among companies with a peer group) | Median # of companies in peer group |

| 97% | 31% | 18 |

While use of a peer group is almost universal among large cap companies, many use a peer group as a reference point when setting pay and do not disclose targeting a specific pay position relative to market. Only half of the companies in our study disclose a target pay philosophy for total compensation. Of these companies, only 7% target total compensation above median.

| Target Pay Philosophy (n = 56) | |||||

| Element | Base | Bonus | Cash | Long-Term Incentives | Total Compensation |

| % Disclosing | 32% | 22% | 22% | 24% | 47% |

| % Target Below Median Pay | 8% | – | – | – | – |

| % Target Median Pay | 87% | 96% | 96% | 97% | 93% |

| % Target Above Median Pay | 5% | 4% | 4% | 3% | 7% |

Annual Incentive

Annual Incentive Plan Metrics

A majority of CAP 120 companies (90%) fund their annual incentive plans using two or more metrics. Only 10% of companies use 1 metric, reflecting a decrease from 2009, as companies try to balance overall plan funding. Use of multiple performance metrics allows for annual incentive payouts to be reflective of broader company performance.

Operating Income (including EBIT, Pre-tax Income and EBITDA), Revenue, EPS, and Cash Flow are the most common metrics used in annual incentive plans. Since our first study, the use of Operating Income and Revenue has been generally consistent. Over this period, the use of EPS, Return Metrics and Net Income has decreased (by 11, 10 and 6 percentage points, respectively).

Note: In the chart above, n/a = not available. Percentages add to greater than 100% due to multiple responses disclosed by many of the companies. Return measures category is comprised of the following metrics: ROE, ROI, ROIC, and ROA.

More companies are incorporating non-financial measures in the annual incentive plan as they are unique to a company’s strategy. Overall, approximately 40% of companies in our study use strategic and other non-financial measures, with certain industries (e.g., Health Care and Oil and Gas) having more of an emphasis on these measures. An emerging trend is to incorporate ESG (environmental, social and governance) metrics in the annual incentive program. Overall, 14 companies (12%) in our study disclosed such measures; environmental measures are most prevalent (8 companies) followed by diversity and inclusion (6 companies).

The chart below shows the three most common metrics by industry in 2018:

| Industry | Metrics | ||

| Metric #1 | Metric #2 | Metric #3 | |

| Automotive (n=11) | Cash Flow (73%) | Op. income / EBIT / EBITDA (64%) | Revenue (36%) |

| Consumer Goods (n=14) | Revenue (71%) | EPS (57%) | Op. income / EBIT (50%) |

| Financial Services (n=7) | EPS (68%) | Return Metrics (43%) | Strategic Goals (43%) |

| Health Care (n=11) | Strategic Goals (64%) | Op. income / Pre-tax Income (55%) | EPS (45%) |

| Insurance (n=12) | Op. Income (58%) | Op. EPS (33%) | Op. ROE (25%) |

| Manufacturing (n=10) | Cash Flow (60%) | EPS (50%) | Op. Income (20%) |

| Oil and Gas (n=11) | Strategic Goals (64%) | Op. Income / EBITDA (55%) | ROIC (36%) |

| Pharmaceuticals (n=11) | Revenue (73%) | Pipeline / R&D (73%) | EPS (64%) |

| Retail (n=11) | Revenue (82%) | Op. Income / EBIT / Pre-tax Income (82%) | Strategic Goals (27%) |

| Technology (n=12) | Revenue (67%) | Cash Flow (50%) | Op. income / Pre-tax Income (50%) |

Note: Percentages reflect the prevalence of companies disclosing the metric.

Award Leverage

CAP reviewed proxy disclosures to understand how companies establish annual incentive payout ranges (i.e., threshold payout and maximum payout expressed as a percentage of the target award). 45% of companies in our study disclose a threshold annual incentive payout at a defined level other than zero. The most common threshold payout for these companies is 50% of target. Other companies start at a 0% payout for threshold performance with payout levels progressing to target.

A majority of companies (84%) disclose a maximum annual incentive opportunity. Most of these companies (74%) have a maximum bonus opportunity of 200% of the target award; only a handful of companies (7) have a maximum payout above 200% of target. We continue to see a decline in the number of companies with a maximum payout above 200% of target (8 companies in 2017 and 11 companies in 2016).

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Long-Term Incentives

Long-Term Incentive Vehicle Prevalence

A vast majority of companies in our study (84%) use multiple long-term incentive vehicles for the most senior executives. Slightly more than half of the companies (55%) use two long-term incentive vehicles, typically delivered through either a long-term performance plan and time-based restricted stock/units (an uptick this year to 58%) or a long-term performance plan and stock options.

The next most common approach is to use three vehicles (29% of companies). A small percentage of companies in our study (16%) use only one vehicle and it is most typically delivered in the form of a long-term performance plan (84%).

Performance-based LTI awards for senior executives is used nearly universally among large cap companies (95%) and the use of stock options has declined to 51% of companies. This contrasts our first study when the use of stock options and performance-based LTI was fairly balanced (79% used performance-based LTI and 73% used stock options). The prevalence of time-based restricted stock/units has remained flat.

LTI Award Mix

Performance-based LTI reflects the largest portion of the LTI mix for the CEO. For the first time in our large cap company study, time-based restricted stock reflects a larger portion of the total LTI mix than stock options. The decrease in the value delivered in stock options has shifted to performance-based LTI in the overall LTI mix. The value delivered in time-based restricted stock/units has been generally flat since 2011.

Restricted Stock / Units (RS/RSU) and Stock Option Provisions

The majority of companies use ratable vesting over a period of three years for time-based RS/RSU awards. Approximately 30% of companies use a vesting schedule of four years or more.

For stock options, most companies use 3-year ratable vesting with a 10-year term.

| Stock Options | |||||||

| Vesting Approach | Vesting (Years) | Term (Years) | |||||

| Ratable | Perf-Based | Cliff | 3 | 4 | > 4 | 10 | < 10 |

| 82% | 2% | 16% | 69% | 26% | 5% | 92% | 8% |

Performance-Based Award Provisions

The payout curve for performance-based LTI awards with upside and downside leverage mirrors the payout curve for annual incentive awards; the most common threshold payout is 50% of target and the most common maximum payout is 200% of target. Unlike annual incentive awards, a large number of companies (41% for long-term plans vs. 26% for annual incentive plans) disclose a threshold payout between 25% – 50% of the target award.

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Performance Metrics

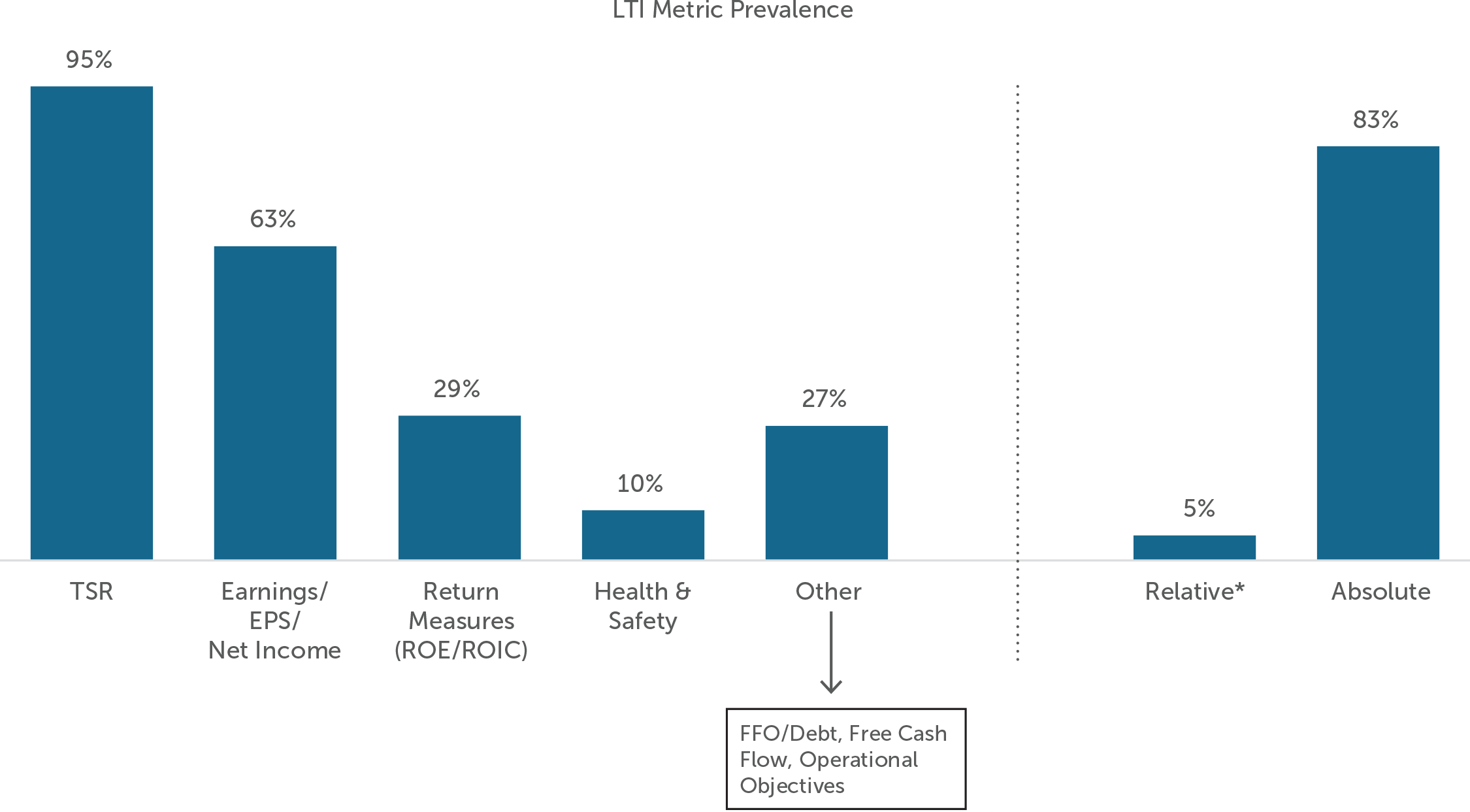

Total Shareholder Return (TSR) continues to be the most prevalent performance metric in long-term performance plans; 63% of companies use it as a measure in the performance-based LTI plan. Return metrics are the second most common measure (51% of companies) followed by EPS (31%) and Revenue (23%).

In CAP’s first study, EPS was the most common measure followed by TSR. The rise in the use of TSR can be linked to the influence of proxy advisors who have increasingly used TSR as a proxy for performance since our first study (conducted prior to the adoption of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act which mandated the shareholder Say on Pay vote). Of the companies that use TSR, approximately 30% disclose using it as an award modifier instead of a weighted metric.

The decline in the use of EPS in performance-based LTI plans is consistent with the decline of EPS use in annual incentive plans. Interestingly, the use of return measures has increased significantly from our first study (51% in 2018 vs. 20% in 2009) as companies are aligning executive long-term pay with profitable growth and operational efficiency. Return metrics are also often favored by institutional shareholders.

Note: Percentages add to greater than 100% due to multiple responses disclosed by many of the companies. Return measures category is comprised of the following metrics: ROE, ROI, ROIC, and ROA.

Performance Measurement – Absolute vs. Relative

A majority of companies in our study balance absolute financial performance goals (based on budget) with relative metrics. This balanced approach has increased substantially since our first study. Today, 52% of companies use both absolute and relative metrics vs. 25% of companies in 2009. This increase is tied to the increase use of relative TSR as a long-term metric.

In our most recent study, only 11% of companies use relative performance metrics only (down from 26% in 2009) and 37% of companies use absolute metrics only (down from 49% in 2009).

Perquisites

A majority of companies in our study (87%) provide perquisites to their CEO. Most companies (69%) also provide perquisites to the CFO. These findings are consistent with our study last year.

Personal use of aircraft, personal security, financial planning and automobile allowance continue to be the most common CEO perquisites. Even though the percentage of companies providing perquisites to the CEO has been relatively flat, the percentage of companies providing the most common perks has increased suggesting that when companies are providing perks to their CEO, it is likely a combination of the four most common categories.

The median value of perquisites delivered to the CEO in 2018 ($125,000) is lower than the value five years ago ($143,000). There was nearly a 30% increase however, in the median perquisite value for the CFO in 2018 ($32,000) compared with 2014 ($25,000).

Stock Ownership Requirement Provisions

Stock ownership guidelines are very common in publicly traded companies and are viewed favorably from a governance perspective. 95% of companies in our sample have requirements in place for the NEOs. For the CEO, the median guideline (expressed as a multiple of base salary) is 6x and for other NEOs it is 3x.

| Stock Ownership

Guideline |

Median Multiple of Base Salary | ||

| CEO | CFO | Other NEO | |

| 95% | 6x | 3x | 3x |

Many companies (52%) have a stock holding requirement in place in addition to the stock ownership guideline requirement for senior executives. It continues to be less common for companies to have stock holding policies that are independent of stock ownership guidelines, or that apply after the ownership requirement has been achieved. These holding policies require executives to hold net shares received from equity awards for periods ranging from one year (most common) to post-retirement. These are generally viewed as shareholder friendly, yet their prevalence has remained fairly consistent over the past few years.

| Holding Requirement Until SOG is Met | Holding Requirement Separate from or After SOG is Met | Holding Period for Separate/Post-SOG Requirements (n=26) | |||

| 1 Year | 5 Years | Until Retirement | Post Retirement | ||

| 52% | 22% | 54% | 4% | 23% | 19% |

For questions or more information, please contact:

Melissa Burek Partner

[email protected] 212-921-9354

Lauren Peek Principal

[email protected] 212-921-9374

Compensation Advisory Partners (CAP) examined 2017 pay levels and financial performance across forty-two companies in the utility industry with median revenue of approximately $6.6B1. CAP analyzed all companies in the Philadelphia Utility Index and the Edison Electric Institute. The study focused on performance trends and external market factors affecting pay practices within the industry.

Key Takeaways

- Adjusted earnings (non-GAAP) were up +6% year-over-year

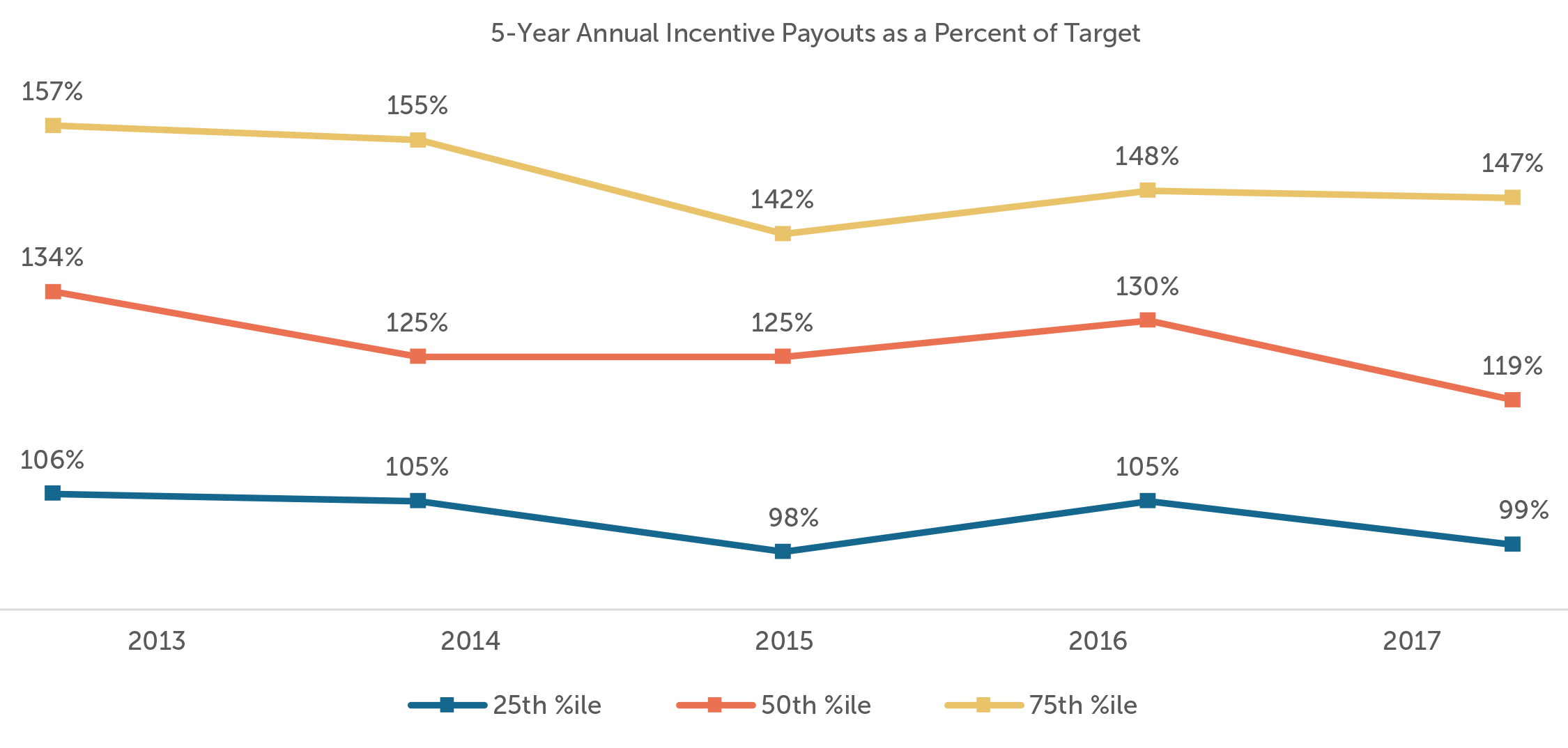

- Median annual incentive payout was above target in both 2016 (130%) and 2017 (119%) reflecting consistently strong performance

- 80% of companies adjusted annual incentive payouts for the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (“Tax Reform”)

- Adjusted (non-GAAP) earnings measures continue to be prevalent metrics in both the short- and long-term incentive plans

- 95% of companies use total shareholder return (TSR) to measure long-term performance

2017 Financial Performance

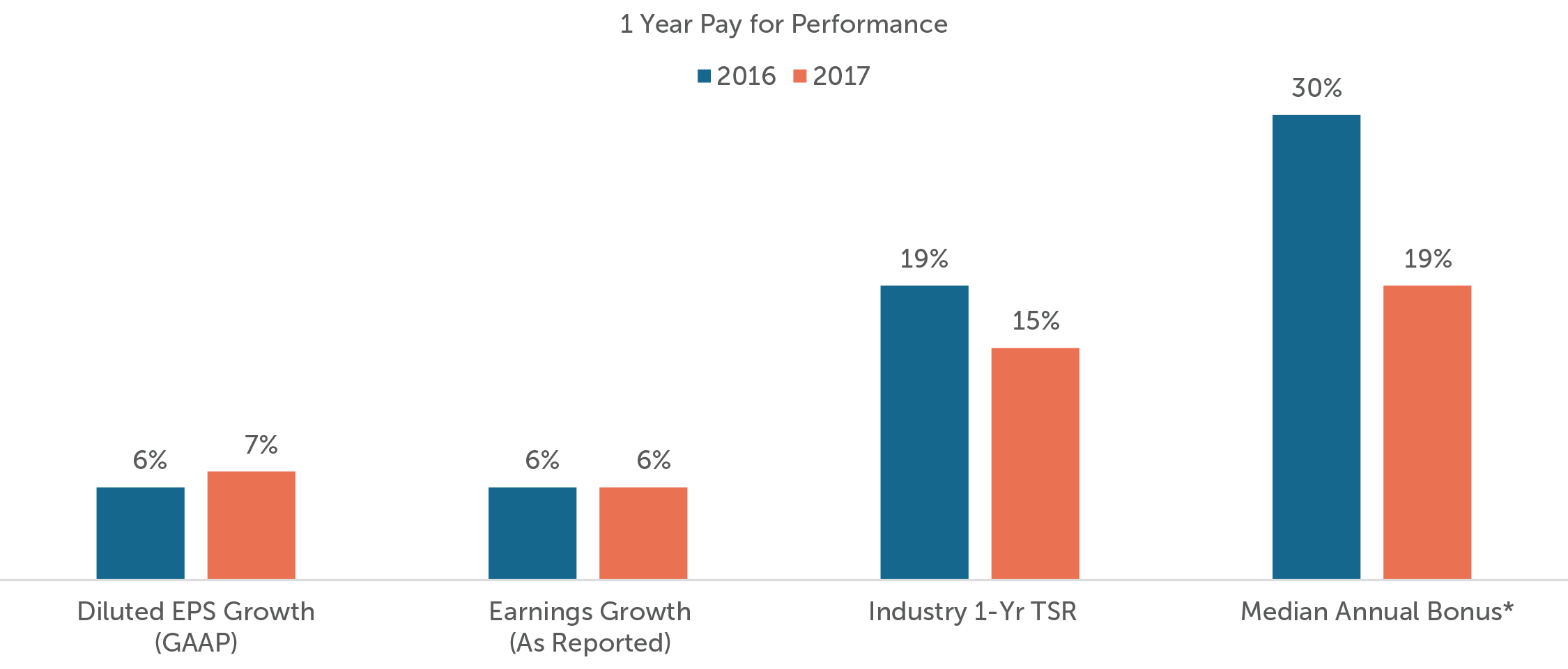

Overall, the utility sector experienced revenue and earnings growth in 2017. Unlike the broader market, utilities are regulated at both the federal and state levels; as regulatory agencies oversee pricing, reliability, and safety. With the rising regulation comes more limited opportunities for revenue growth. Further, given the non-cyclical nature of the utility industry, utilities generally under-perform bull markets and over-perform bear markets. Utilities saw strong TSR of +15% for the year, compared to +20% for the S&P 500; however, year-to-date TSR (as of August 31, 2018) has slowed, with a median return of +4% for the utility industry and +6% for the S&P 500. Revenue and diluted EPS growth for utilities were also up year-over-year, at +4% and +7%, respectively.

Companies saw their financial results impacted by the Tax Reform signed by President Trump in December 2017. Reported (adjusted) non-GAAP earnings for the companies in our sample reflect modest growth (+6%). This slight difference compared to GAAP earnings is partially due to Tax Reform. Many companies experienced a positive impact on their financials, reflected in GAAP numbers, but adjusted numbers would likely eliminate this boost as it was an unknown when budgets were set at the beginning of the year. Return on average capital was also up in 2017 (+3%) compared to +2% in 2016. Overall, despite weaker performance as compared to the S&P 500 index, the utilities industry had a positive year, as evidenced by above-target annual incentive payouts.

| Industry Group | 2017 Median Company Performance | ||

| Revenue Growth | Diluted EPS Growth | TSR | |

| Utilities Cos. (n=42) | + 3.6% | + 7.2% | + 15.1% |

| S&P 500 | + 6.7% | + 9.5% | + 19.8% |

Source: S&P’s Capital IQ

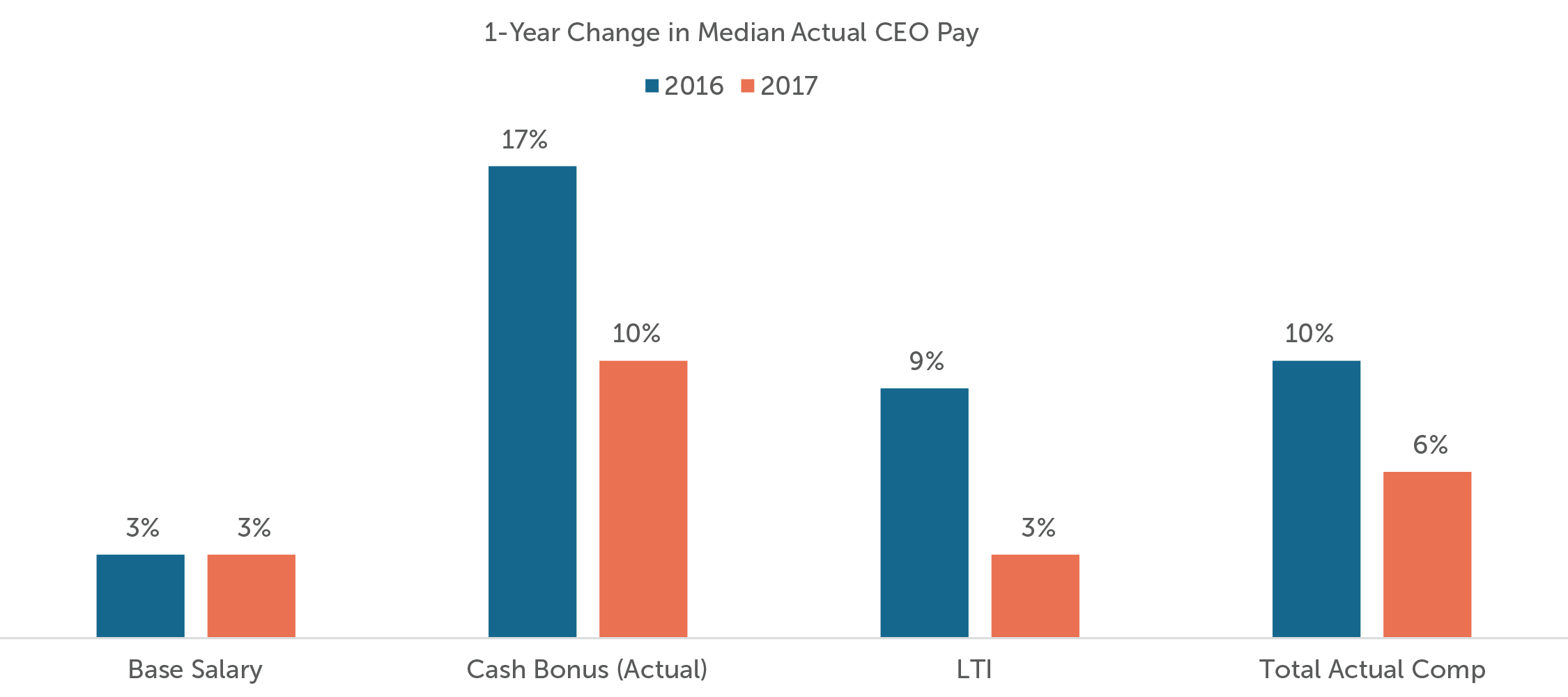

Our study examined the annual change in actual total compensation, which includes the sum of salary, 2017 bonus payments (paid Q1 2018) and the grant date value of 2017 long-term incentives (LTI) for CEOs who have been in their position for both 2016 and 2017. Total compensation increased by approximately 6%, driven primarily by an increase in cash bonuses. Last year, we saw larger increases in both LTI (+ 9%) and in cash bonuses (+ 17%) resulting in a 10% increase in total compensation.

*Reflects performance payout above target.

Utilities generally pay out annual incentives above target. In our sample, at least 75% of companies’ 5-year average payout was above target with a median 5-year average of 122%. CAP’s research suggests that in the broader market, companies and committees generally set goals with a degree of difficulty so that there is a 60-65% chance of achieving at least target performance. While it is not uncommon to continually pay out at or above target, utility companies do it at a higher rate than companies in other industries. This is partially due to a more predictable business model, so they rarely pay zero bonus, but also do not pay maximum very often.

Annual Incentive Plans – Adjustments

The most common metric among utilities continues to be earnings metrics (EPS, EBITDA, etc.) as it most directly correlates with the operations of the business. As is common in the broader market, nearly all companies use an adjusted metric. It is reasonable to adjust for variables outside of management’s control but adjusting for too many variables can lead to a disconnect between pay and performance and causing misalignment with shareholders. Further, ISS and Glass Lewis use GAAP metrics in their pay for performance models, so it is important to test their models using GAAP metrics to ensure there is no pay for performance misalignment.

Utilities generally adjust for mark-to-market fluctuations, closing of plants, merger/integration costs, cost saving initiatives, regulatory charges, operations and maintenance expenses, and nuclear decommissioning trust. These are the most common adjustments as management has limited ability to impact the way these variables affect metrics. CAP found that 90% of companies in our sample adjust for at least one of these variables.

Additionally, 80% of companies who made adjustments to incentive metrics also adjusted out the positive impact of Tax Reform as this was not anticipated at the time goals were set at the beginning of the year. Companies and committees felt they should not get the benefit of the positive impact.

Annual Incentive Plans – Goal Setting

While profitability measured on a GAAP basis was up +7%, on a reported basis, earnings increased +6%, which aligns with above target bonus payouts in 2017.

It continues to be a trend in goal-setting among utilities to set targets lower than prior year target or actual performance, given the variables of the industry that are beyond management control (i.e., declining prices, changes in demand, etc.). This particular issue of goal-setting continues to be an area of concern for proxy advisory groups. However, continual higher performance can be challenging in the industry and setting unattainable targets can negate the effectiveness of incentives. When setting targets, management may have a better sense of the more “predictable” adjustments, but actual performance reflects the volatility of the business and unpredictable outcomes that are not foreseen in the target-setting process. Among the companies in our sample, 24% of companies set 2017 targets below 2016 targets and 25% set 2017 targets below 2016 actual. This is compared to 40% and 44%, respectively, for 2016 targets.

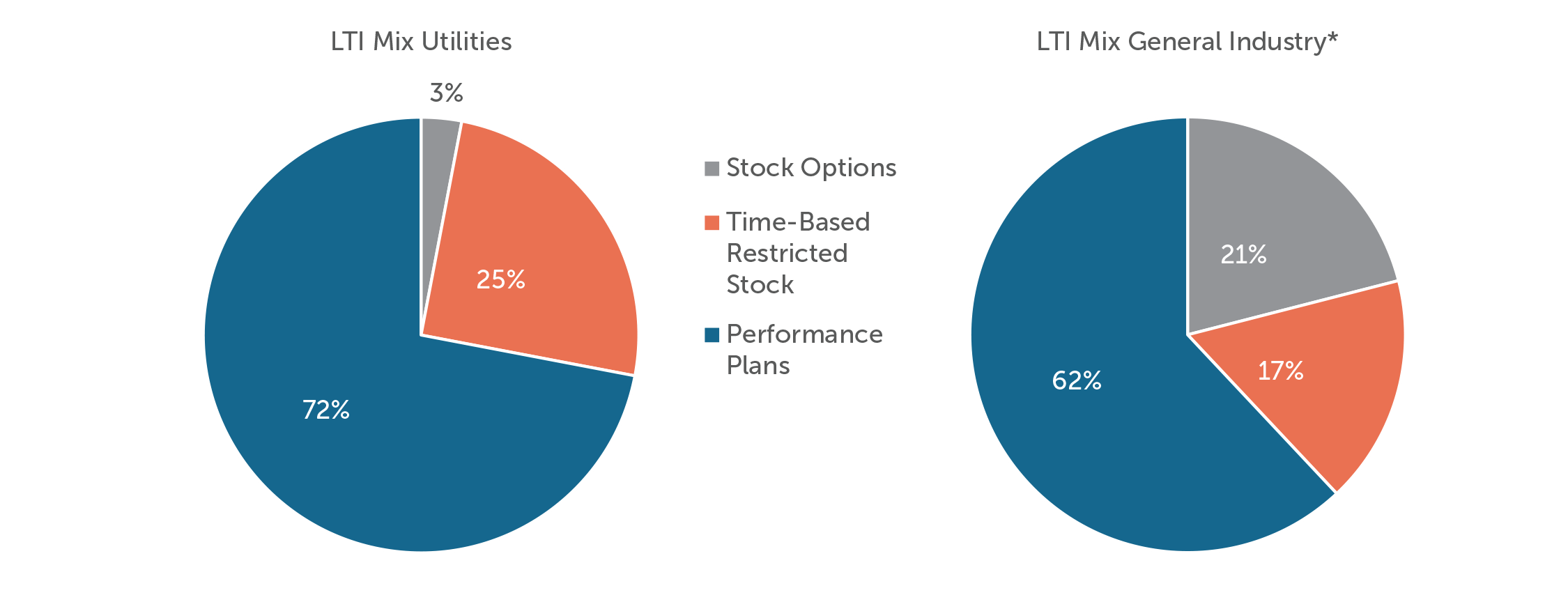

Long-Term Incentives – Emphasis On Longer Term Performance Plans

Utilities companies long-term incentive plans place strong emphasis on performance-based compensation with 90% of companies placing at least 50% weight on a performance plan. Only one company in our sample does not use a performance plan in their long-term incentives. These companies also place more emphasis on time-based restricted stock and less emphasis on stock options as compared to the broader market (only 5 companies grant stock options in our sample).

*Compensation Advisory Partners 100 Company Database

Most companies use a 3-year performance period. As a result, companies are linking executive pay with long term performance, measured most often by Relative TSR or EPS vs. plan; all but three companies use relative TSR in their long-term incentive plans. The most common comparator group is the compensation peer group; however, over half the companies measure against an index.

TSR Comparator Groups

| Comparator Group | Prevalence (% of companies) |

| Compensation Peer Group | 28% |

| Edison Electric Institute | 24% |

| S&P 500 / S&P 1500 / S&P 400 Mid-Cap Utilities | 18% |

| Performance Peer Group | 15% |

| Philadelphia Utility Index | 15% |

Of the 21 companies with EPS in their long-term incentive program, 67% also use it as a metric in their short-term incentive program. This double-use can be an area of concern for select shareholders and is often raised by proxy advisors, especially when pay and performance are misaligned. However, these companies typically use different targets for the metric when both annual operating targets and long-term strategy are key areas of focus and we believe this can often be effective in reinforcing priorities.

*Excludes relative TSR metrics

Conclusion

After experiencing a relatively slow period of growth over the last several years, the utility industry is expected to pick up over the next few years. The industry, as a whole, is expected to face several conflicting factors. Increased energy efficiency will slow consumption, but demand for power is expected to increase, particularly in connection with an increase in new housing construction. With an increase in demand and an anticipated increase in prices, utility companies can expect to see profit growth over the next few years. The utility industry increase is expected to track with the greater macroeconomic growth anticipated in this period. On the other hand, regulation is expected to increase, slowing profit growth.

The removal of the Clean Power Plan, in addition to the expiration of the Federal Investment Tax Credit and Production Tax credit will slow the high growth that renewable energy has seen over the last couple of years. Despite this, many states are expected to continue to implement renewable portfolio standards which will lead to more energy creation from renewable resources. With the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) removal of the Clean Power Plan, electric power operators may be less likely to move away from coal production (compared to if it had stayed in place) but with natural gas prices expected to remain low, coal-power generation companies will continue to face challenges.

Management and Boards of companies in this industry must continue to monitor the changing environment and maintain a corporate strategy and goals that will allow success in the highly regulated environment. The continued use of non-GAAP metrics in incentive plans will aid proper incentivization for executives in the challenging market, but adjustments should only be made for factors outside management’s control or were unforeseen in the goal-setting process (i.e., tax reform). The biggest struggle companies will face with shareholders and proxy advisory firms is ensuring that appropriate financial goals are being set in both the business plan and incentive plans for executives.

Additional Information – New Ceo Pay Ratio Disclosure

All of the companies in our sample were required to disclose the ratio of their CEO pay to that of the median employee in 2018. The utility industry saw some of the lowest pay ratios across all companies. CEO pay in our sample ranged from 15x to 190x, with a median of 64x that of the median employees’ pay. The lower ratios compared to the broader market are due to primarily US workforces and high percentages of unionization among the employee population, resulting in much higher median employee pay as compared to other industries (median pay of $122k). Given the flexibility that companies have in the methodology and assumptions used to calculate the ratio, comparisons of ratios between companies are less meaningful. To date, institutional investors and proxy advisory firms have not used disclosed CEO pay ratios to inform their voting decisions. We may see some year-over-year comparisons in the second year of disclosure.

For questions or more information, please contact:

Dan Laddin Partner [email protected] 212-921-9353

Shaun Bisman Principal [email protected] 212-921-9365

Joanna Czyzewski Associate [email protected] 646-486-9746

Robert Martin and Diane Lee provided research assistance for this report.

Exhibit 1

- ALLETE, Inc.

- Alliant Energy Corporation

- Ameren Corporation

- American Electric Power Company, Inc.

- American Water Works Company, Inc.

- Avangrid, Inc.

- Avista Corporation

- Black Hills Corporation

- CenterPoint Energy, Inc.

- CMS Energy Corporation

- Consolidated Edison, Inc.

- Dominion Energy, Inc.

- DTE Energy Company

- Duke Energy Corporation

- Edison International

- El Paso Electric Company

- Entergy Corporation

- Eversource Energy

- Exelon Corporation

- FirstEnergy Corp.

- Hawaiian Electric Industries, Inc.

- IDACORP, Inc.

- MDU Resources Group, Inc.

- MGE Energy, Inc.

- NextEra Energy, Inc.

- NiSource Inc.

- NorthWestern Corporation

- OGE Energy Corp.

- Otter Tail Corporation

- PG&E Corporation

- Pinnacle West Capital Corporation

- PNM Resources, Inc.

- Portland General Electric Company

- PPL Corporation

- Public Service Enterprise Group Incorporated

- Sempra Energy

- The AES Corporation

- The Southern Company

- Unitil Corporation

- Vectren Corporation

- WEC Energy Group, Inc.

- Xcel Energy Inc.

1 See Exhibit 1 for list of companies included.

Compensation Advisory Partners (CAP) examined 2016 executive pay and company performance at 29 companies in the utility industry with median revenue of approximately $10B. The study focused on performance trends and external market factors affecting pay practices within the industry.

2016 Financial Performance

Overall, the utility sector performed well versus the broader market. Utilities saw strong total shareholder returns (TSR) of +19% for the year versus the S&P 500 index of +12% for 2016. The impact of the 2016 U.S. presidential election on the market helped drive the strong returns. Specifically, the potential for pro-growth policies related to economic stimulus, tax reform and reduced regulations, led to a significant impact on the shareholder returns of certain industries, such as financial services. However, the utilities industry underperformed the S&P 500 with TSR finishing out the year flat following the election compared to +5% gain for the S&P 500. This may be a result of investors repositioning their portfolios away from utilities, in anticipation of potential pro-growth policies from the Republican controlled government. Now, nearly midway through 2017, with some delays in potential regulatory changes, utilities TSR year to-date (as of 5/31/17) of +13% is outpacing the S&P 500 (+9%).

Companies use annual bonuses as a tool to reward executives for achieving short-term financial and strategic goals. Setting appropriate annual performance goals is essential to establishing a link between pay and performance. Goals should achieve a balance between rigor and attainability to motivate and reward executives for driving company performance and creating returns for shareholders.

Key Takeaways:

- Based on our analysis of actual incentive payouts over the past 6 years, the degree of difficulty, or “stretch”, embedded in annual performance goals translates to:

- A 95% chance of achieving at least Threshold performance

- A 75% chance of achieving at least Target performance

- A 15% chance of achieving Maximum performance

- This pattern indicates that target performance goals are challenging, but attainable, and maximum goals are achievable through highly superior performance

- The majority of companies use two or more metrics when assessing annual performance

- Annual incentive payouts have been directionally linked with earnings growth over the past 6 years

Summary of Findings

Plan Design

For the purposes of this study, we categorized annual incentive plans as either goal attainment or discretionary. Companies with goal attainment plans define and disclose threshold, target and maximum performance goals and corresponding payout opportunities. Alternatively, companies with discretionary plans do not define the relationship between a particular level of performance and the corresponding payout. Discretionary programs provide committees with the opportunity to determine payouts based on a retrospective review of performance results.

| Annual Incentive Plan Type | |||

| Industry | Sample Size | Goal Attainment | Discretionary |

| Auto | n= 8 | 100% | 0% |

| Consumer Discretionary | n= 10 | 90% | 10% |

| Consumer Staples | n= 12 | 67% | 33% |

| Financial Services | n= 12 | 17% | 83% |

| Healthcare | n= 9 | 89% | 11% |

| Industrials | n= 14 | 71% | 29% |

| Insurance | n= 12 | 67% | 33% |

| IT | n= 12 | 83% | 17% |

| Pharma | n= 10 | 80% | 20% |

| Total | 72% | 28% | |

Consistent with the findings from our study conducted in 2014, 72% of sample companies have goal attainment plans. Our study focuses on these companies.

Performance Metrics

Most companies (61%) use 3 or more metrics to determine bonus payouts. This reflects a shift from 2014, where 48% of companies used 3 or more metrics. Companies annually review metrics to ensure that they align with the business strategy.

Many companies use financial metrics such as revenue and profitability, which are indicators of market share growth and stock price performance. Some bonus plans also include strategic metrics, which incentivize executives to achieve goals that may contribute to long-term success, but may not be captured by short-term financial performance. Companies in the pharmaceutical industry often use strategic goals, such as pipeline development. Similarly, companies with large manufacturing operations often use quality control metrics.

| # of Metrics Used in Goal Attainment Plan | ||||

| Industry | 1 Metric | 2 Metrics | 3 Metrics | 4+ Metrics |

| Auto | 13% | 13% | 25% | 50% |

| Consumer Discretionary | 11% | 44% | 45% | 0% |

| Consumer Staples | 0% | 37% | 38% | 25% |

| Financial Services | 0% | 50% | 50% | 0% |

| Healthcare | 0% | 38% | 12% | 50% |

| Industrials | 20% | 40% | 20% | 20% |

| Insurance | 37% | 13% | 25% | 25% |

| IT | 10% | 30% | 40% | 20% |

| Pharma | 0% | 0% | 63% | 37% |

| Total | 11% | 28% | 34% | 27% |

Pay and Performance Scales

Compensation committees annually approve threshold, target, and maximum performance goals, and corresponding payout opportunities, for each metric in the incentive plan. Target performance goals are typically set in line with the company’s internal business plan. Executives most often earn 50% of their target bonus opportunity for achieving threshold performance and 200% for achieving maximum performance. Actual payouts are often interpolated between threshold and target and target and maximum.

Annual Incentive Plan Payouts Relative to Goals

All Companies

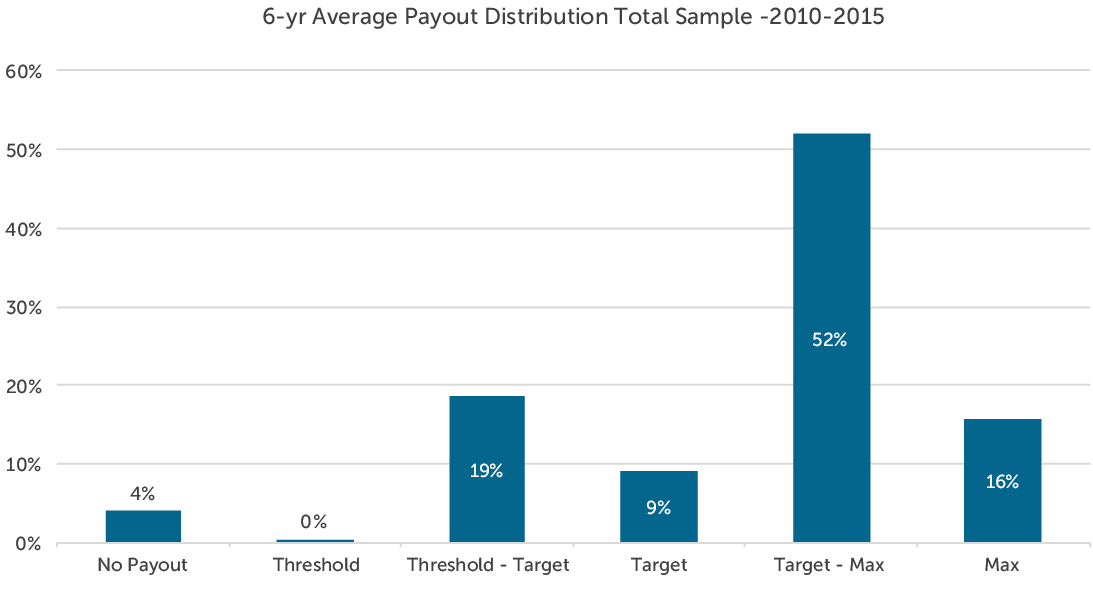

Based on CAP’s analysis, companies paid annual bonuses 95% of the time. Payouts for the total sample are distributed as indicated in the following charts:

This payout distribution indicates that committees set annual performance goals with a degree of difficulty or “stretch” such that executives have:

- A 95% chance of achieving at least Threshold performance

- A 75% chance of achieving at least Target performance

- A 15% chance of achieving Maximum performance

From 2010-2015, no more than 10% of companies failed to reach threshold performance in any given year. By comparison, in both 2008 and 2009, which were challenging years, approximately 15% of companies failed to reach threshold performance goals.

When looking back over 8 years (2008-2015), companies achieved at least threshold and target performance with slightly less frequency. Based on CAP’s analysis of this 8-year period, executives have:

- A 90% chance of achieving at least Threshold performance

- A 70% chance of achieving at least Target performance

- A 15% chance of achieving Maximum performance

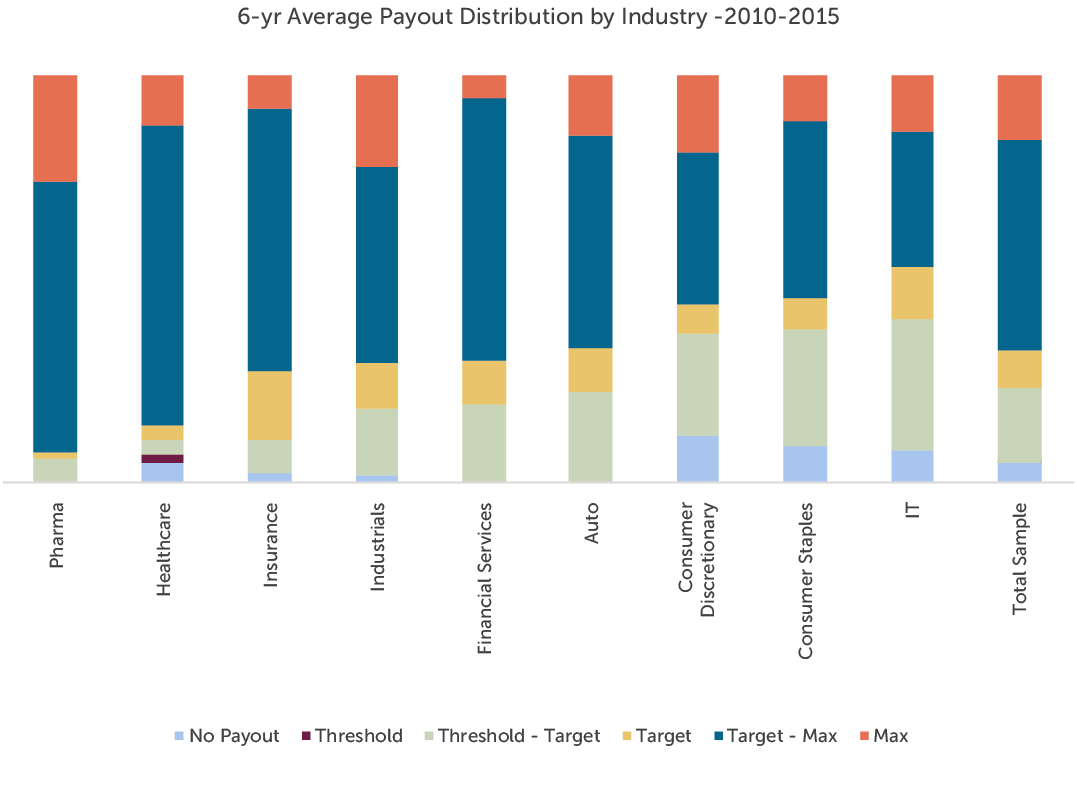

By Industry

Pharmaceutical and healthcare companies have paid at or above target more frequently than companies in any other industry over the past 6 years. Both industries have experienced significant growth over the period in part due to consolidation. The companies in the IT, Consumer Discretionary and Consumer Staples industries tend to pay below target at a higher rate. Average payouts for each industry are distributed as indicated in the following chart:

Relative to Performance

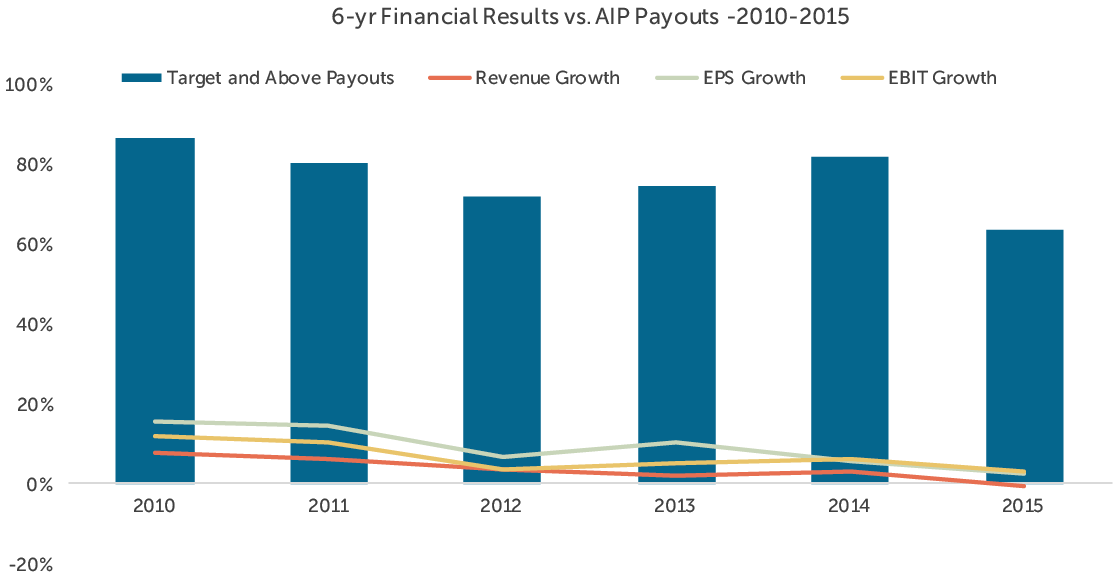

CAP reviewed the relationship between annual incentive payouts and company performance with respect to three metrics: revenue growth, earnings per share (EPS) growth and earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT) growth. While payouts were generally aligned with revenue and EPS growth, they most closely tracked with EBIT growth over the period studied (2010-2015). Companies may seek to align bonus payouts with operating measures, such as EBIT, as they capture an executive’s ability to control costs and improve operational efficiency.

The chart below depicts the relationship between median revenue, EPS, and EBIT growth and target and above annual incentive payouts among the companies studied.

Conclusion

In the first quarter of 2017, committees will certify the results and payouts for the fiscal 2016 bonus cycle and approve performance targets for fiscal 2017. Given the uncertain economic outlook following the 2016 presidential election, establishing performance targets for 2017 may be more challenging than usual. Companies may choose to use a range of performance from threshold to maximum to build flexibility into their plans given the unpredictable environment. Our study of annual bonus payouts over the past 6-8 years supports setting goals such that the degree of difficulty, or “stretch”, embedded in performance goals translates to:

- A 90-95% chance of achieving at least Threshold performance

- A 70-75% chance of achieving at least Target performance

- A 15% chance of achieving Maximum performance.

Companies should continue to set target performance goals that are challenging, but attainable and maximum goals that are achievable through outperformance of internal and external expectations – therefore, establishing a bonus plan that is attractive to executives and responsible to shareholders.

Methodology

CAP’s study consisted of 100 companies from 9 industries, selected to provide a broad representation of market practice across large U.S. public companies. The revenue size of the companies in our sample ranges from $18 billion at the 25th percentile to $70 billion at the 75th percentile.

CAP analyzed the annual incentive plan payouts of the companies in the sample over the past 6-8 years to determine the distribution of incentive payments and the frequency with which executives typically achieve target payouts. In this analysis, CAP categorized actual bonus payments (as a percent of target) into one of six categories based on the following payout ranges:

| Payout Category | Payout Range |

| No Payout | 0% |

| Threshold | Up to 5% above Threshold |

| Threshold – Target | 5% above Threshold to 5% below Target |

| Target | +/- 5% of Target |

| Target – Max | 5% above Target to 5% below Max |

| Max | 5% below Max to Max |

Spin-offs have been in the news for several years. Fully 60 spin-off transactions occurred in 2014, followed by another 40 spin-offs in 2015, with 13 involving S&P 500 companies.1 Spin-off activity continued to be newsworthy in 2016 with major spin-offs completed by Alcoa, Danaher, Emerson Electric, Johnson Controls, and Xerox. Spin-off activity will continue into 2017 with a number of pending transactions including major companies like Ashland, Biogen, Hilton Worldwide, and MetLife. The need to create shareholder value during a period marked by low returns from most asset classes is driving the spin-off activity. In some cases, activist shareholders have pushed companies to create value by breaking businesses into their component parts. When a business undergoes a spin-off, the human resource and executive compensation implications for executives at both the Parent Company (ParentCo) and the Spin-off Company (SpinCo) are very significant.

We have advised many companies as they worked through the spin-off process and we want to share some of what we have learned. As a starting point, we have identified four critical work streams for executive compensation in a spin-off:

- Establishing Transitional Compensation Arrangements (e.g., near-term retention plans)

- Understanding and/or Modifying Outstanding Compensation Arrangements (e.g., outstanding equity awards, severance and change in control agreements, benefit plans, etc.)

- Developing Going Forward Compensation Programs for SpinCo, equivalent in many ways to standing up a newly public company in an IPO

- Modifying Compensation Programs for ParentCo, as necessary to reflect new business focus and business scale

1. Establishing Transitional Compensation Arrangements

After deciding that a portion of the business is going to be spun-off, one of the first compensation decisions that needs to be addressed is how to structure incentive compensation programs for the company in the year of the spin-off. How complex this step is will depend on the timing of the spin-off in the fiscal year and the nature of the company’s annual and long-term incentive plans. A general principle is that if the spin-off has already been announced at the time design decisions are being made, SpinCo incentive compensation should be based primarily on SpinCo performance to provide better line-of-sight for SpinCo employees and to facilitate the transition.

Annual Incentive Plans

If the upcoming spin-off is a known event at the time that the annual incentive award is made, the transitional incentive plan can be simplified by ensuring that the annual incentive for SpinCo executives is tied 100% to SpinCo performance for the entire fiscal year. In this case, SpinCo executives will be paid an annual incentive based on SpinCo’s performance early in the fiscal year following the spin-off.

In some cases, the annual incentive award may already have been granted prior to the announcement of the spin-off. In such a situation, it is likely that the incentive plan for SpinCo employees will be based on a combination of ParentCo and SpinCo performance up to the time of the spin-off and then on SpinCo performance for the remainder of the year. This may require the company to establish SpinCo specific performance goals for the “stub period” from the completion of the spin-off to the end of the fiscal year. The performance measures for the “stub period” are typically the same performance measures used to assess SpinCo performance for the portion of the fiscal year prior to the completion of the spin-off.

Long-term Incentive Plans

Similar to the short-term incentive, if the company knows that the spin-off is going to take place during the fiscal year, there are design decisions that can help to facilitate transitioning the long-term incentive awards. For any performance-based awards (e.g., performance shares/units/cash), SpinCo employees should be granted awards that are based on multi-year performance objectives for the SpinCo. In some cases, companies will avoid making performance-based awards to SpinCo employees in the year of the transition because of the challenges in maintaining a consistent performance measurement approach before and after the spin-off.

If the spin-off is not a known event at the time that performance awards are made, there may be challenges in converting ParentCo performance awards into SpinCo performance awards at the time of the spin-off. In these cases, some companies will truncate the payout based on the ParentCo performance to date, at spin, and establish SpinCo goals for the remainder of the overall performance period. We will address this issue in greater detail in the next section on the treatment of outstanding awards following the spin-off.

Special Transition Compensation Programs

Most SpinCo employees are likely to view the spin-off as a positive event. Staff positions (e.g., finance, legal, human resources, etc.) will often have enhanced roles and responsibilities at the new company, given the stand-alone nature of the business. Line positions (e.g., business unit executives and staff) often feel that the spin-off provides them with a greater ability to impact business performance.

On the other hand, announcement of a spin-off creates uncertainty about the future prospects of the business. In addition, the SpinCo is a potential acquisition target, with the business potentially being sold rather than spun-off to shareholders. In many cases, it makes sense to review the severance protection in place for SpinCo staff in advance of announcing the spin-off. If there is a real chance that the business may be sold, enhanced severance protection may be needed to ensure that staff positions do not “jump ship”.

There may also be employee retention concerns at the ParentCo. While the spin-off is generally a positive event for SpinCo employees, spin-offs can create concerns for ParentCo employees. For ParentCo employees, a spin-off means working for a smaller company in the future, with a less complex and potentially less interesting job. In addition, the spin-off transaction will create additional work for all corporate staff positions as they set up the newly public company and continue to do their “day job”. For select ParentCo employees, a near-term retention bonus or short-term stock retention grant may provide recognition for their additional workload and focused efforts on preparing for a successful transaction, and help to keep them engaged in a stressful working environment. To the extent that certain corporate staff positions will no longer be needed following the spin-off, there may also be a need for enhanced severance for corporate staff.

2. Understanding and/or Modifying Outstanding Compensation Arrangements

As the company approaches the spin-off, a key compensation issue is how to adjust outstanding compensation arrangements to recognize that one company is breaking up into two companies. Decisions need to be made about what will happen to the company’s long-term incentive plans, as well as retirement plans and deferred compensation plans. For purposes of this discussion, we will focus on long-term incentive plans, as it is an area that is particularly critical for executive compensation.

The treatment of outstanding long-term incentives (particularly equity incentives), can be complex following a spin-off. There are several steps that need to be taken to transition awards, including review of the following:

- What provisions are specified in the equity plan and equity award agreements?

- Should the Committee apply discretion to modify the treatment of employees’ awards based on the circumstances of the transaction?

- What is the preferred approach for converting ParentCo equity (i.e., ParentCo post-spin and SpinCo equity)?

- What will be the timing of the conversion of equity?

Existing Equity Plan and Award Agreements

The first step in reviewing outstanding equity is to understand the treatment that the company’s equity plan and the individual award agreements prescribe for outstanding equity awards. A key issue to understand is what will happen to the awards held by employees of SpinCo. In many cases, the spin-off constitutes a termination of employment and, under ParentCo’s plans, unvested awards are forfeited at the spin-off.

It is important to understand the extent to which the prescribed approach impacts the bottom line of both entities. It is also important to work with internal and external counsel to ensure that there is a common understanding of the contractual rights of employees under the equity plan and award agreements.

Another key issue is whether the plan provides for the conversion of outstanding awards in a spin-off transaction. The plan document will likely include a section addressing a change in capital structure and transactions like a spin-off. In most cases, the Committee is required to convert vested awards to preserve value, but is afforded significant latitude in determining the details of the conversion.

Exercise of Compensation Committee Discretion

In our experience, most Compensation Committees do not want SpinCo employees to forfeit outstanding unvested equity as a result of a spin-off transaction. Forfeiture of previously awarded equity could have a serious impact on morale. One way to address this is to accelerate vesting in ParentCo equity or to provide for continued vesting post-spin. Alternatively, if the ParentCo’s Compensation Committee does not take action to keep SpinCo’s employees whole, then SpinCo’s Compensation Committee may need to take action following the spin-off. But it is important to keep in mind that each situation is different. If outstanding awards are underwater, the spin-off may be an opportunity to eliminate overhang on the stock.

Approaches for Conversion of ParentCo Equity

There are several approaches that are used in practice when addressing how to treat outstanding equity upon a spin-off. The following table provides an overview of the alternative approaches:

|

Approach |

Description |

|

Employee |

Employee awards are converted to equity in the company where they are employed. The participants of the equity plan who remain employed by ParentCo retain adjusted ParentCo equity awards. The equity plan participants who are employed by SpinCo receive converted SpinCo equity awards with same terms and conditions |

|

Shareholder |

Employees are treated like shareholders. Regardless of where the participant is employed following spin-off, outstanding awards of all equity plan participants are converted into both ParentCo and SpinCo equity at the same conversion ratio as shareholders, with the same terms and conditions as the original awards |

|

Hybrid |

A combination of the “Employment” and “Shareholder” approaches based on any of the following: (i) when the equity award was granted, (ii) where the equity holder is employed post-spin, (iii) when the equity award will vest, and/or (iv) the type of equity held at spin-off |

|

Adjustment Only, No Conversion Approach |

All employees retain adjusted ParentCo equity with same terms and conditions. Continued employment with SpinCo is treated as employment with ParentCo, for purposes of continued award vesting |

While several approaches to conversion are used in practice, the Employee approach is the most consistent with the goal of aligning the executives of the company with the shareholders of the entity they support following the spin-off. Other approaches (e.g., shareholder) may attempt to recognize the efforts of employees, prior to the spin, given that such efforts contribute to the future business success of both entities, post spin. The hybrid approach is sometimes used in situations where there is a significant difference in the growth prospects of the SpinCo or ParentCo. (i.e., ParentCo is expected to have modest price appreciation potential and SpinCo has strong growth prospects). And it is sometimes the case that different treatments may apply to employees within one entity. For example, if the ParentCo hires a senior executive for SpinCo from outside the company, prior to the spin, their awards may convert using the Employee approach if they have minimal service at ParentCo, yet the Shareholder approach may be used for other employees.

For outstanding long-term performance share or unit/cash plans (typically with three-year performance cycles), practice is mixed, and the conversion approach used will depend on the length of time remaining in the outstanding award cycle, the performance measures used, whether a new program is put in place in SpinCo, and the type of SpinCo company structure. In many cases, ParentCo prorates outstanding LTI awards held by employees of SpinCo to reflect their time as an employee of ParentCo. The prorated awards held by SpinCo employees are then paid out based on the original performance criteria at the time payments are made to ongoing employees of ParentCo. Once employees have transferred to SpinCo, the remaining stub periods of each outstanding award may be paid out at the target award amount, or, in cases where the Committee of SpinCo wants to preserve a performance-based focus, they may establish new performance goals based on operational or stock performance of SpinCo. There are challenges associated with setting goals for these ‘interim’ performance periods, yet many companies will do so.

Retirement Programs. Agreement on the treatment of retirement programs, non-qualified deferred compensation (“NQDC”) plans and other benefits is a critical administrative decision. If ParentCo has a defined benefit plan, it must determine whether to transfer assets and liabilities of the pension associated with SpinCo employees to SpinCo. A decision on whether any applicable grandfathering of frozen plans/plan benefits will continue is also required. Non-qualified benefit programs are often only partially funded, or unfunded, and the amounts can be significant. Typically, employee accounts in any NQDC plan of ParentCo are transferred to a SpinCo plan for employees of SpinCo. Alternatively, SpinCo could receive a payout of the NQDC applicable balances. Plan provisions will dictate the course of action. Note that distributions in connection with a spin-off are generally not compliant with Section 409A of IRC, since a spin-off is not a separation of service for employees under 409A.

Health and Welfare Benefits. Generally, SpinCo is responsible for setting up new health and welfare programs and both ParentCo and SpinCo are responsible for claims incurred against the respective plans post-spin. Certain programs such as retiree medical, however, may require a determination of how to allocate liabilities to SpinCo (e.g., for current terminated employees, or just future retirees). Decisions on allocating liabilities related to LTD payments, accrued vacation, COBRA, workers’ compensation, etc. may also need to be made depending on the programs of ParentCo.

Severance and Change in Control (“CIC) Benefits. A spin-off could trigger a CIC depending on the provisions of ParentCo’s various plans. While many benefits arising from a CIC are only paid after a “double trigger” (i.e., they are only paid or vested if a termination of employment occurs in connection with the CIC), certain benefits may be accelerated or payments may be triggered immediately. As a result, severance payments could become due to employees transferring to SpinCo. The companies need to determine if any severance obligations apply when employees transfer to SpinCo and who bears the responsibility for such obligations. Note however, that in many transactions, outstanding awards are assumed by SpinCo, in which case, payments would not be accelerated, nor would any benefits be distributed.

3. SpinCo Going Forward Compensation

Developing a going forward compensation program for the SpinCo is a critical process that often evolves over time. While the default approach may initially be to maintain compensation programs similar to those of the parent company, there may be a compelling case to make fundamental changes to the compensation program to address differences between the SpinCo and the Parent. However, depending on the time-frame for completion of the spin-off and the corporate governance structure, the timing of any such changes may be delayed.

Corporate governance of a spin-off can vary and we have seen each of the following approaches used:

- SpinCo Board of Directors is led by ParentCo executives through time of spin-off until ParentCo no longer has majority stake

- SpinCo has Independent Board members appointed prior to spin-off; decisions on compensation for SpinCo may be subject to Parent Company Compensation Committee approval

- ParentCo Compensation Committee reviews and approves programs for SpinCo

Prior to a planned spin-off there is typically a designated subcommittee of the Parent company board that begins planning and making decisions related to the SpinCo’s compensation program. A Lead Director may be appointed to oversee this planning process on behalf of the new Board, working with the company’s HR or designated SpinCo CEO. Prior to the spin-off, coordinated efforts to recruit new directors, develop a compensation committee charter and a Board calendar, etc. are required.

In a one-stage spin-off, where all shares of the SpinCo are distributed to ParentCo shareholders at the time of the spin-off, the involvement of ParentCo executives and Board members in SpinCo corporate governance will cease at the time of the spin-off. In other cases, where the SpinCo is distributed in stages (e.g., partial IPO to public shareholders followed by a completion of the spin-off or incremental sale of shares in the SpinCo to the public), the parent company Board or parent company executives may continue to serve as Board members of the SpinCo up until the time that the parent company has fully distributed its interest in SpinCo.

When ParentCo Board members or executives are involved in the compensation design, they are more likely to fall back on maintaining a compensation approach that is consistent with that of the parent. They may continue to view the SpinCo as akin to a subsidiary. In these cases, the SpinCo’s compensation program may evolve from the timing of the initial spin-off through the year following the parent company fully divesting its interests in the SpinCo.

Pay Philosophy and Target Pay Levels

For the SpinCo, there is typically pre-planning around the desired compensation philosophy, including a defined market or peer group for pay and performance benchmarking. This peer group should be size and industry specific, reflective of the operating characteristics of SpinCo and may or may not include similar peers to ParentCo’s peers.

There is often extensive benchmarking conducted before the spin-off to determine competitive pay levels for executive positions at SpinCo, assuming new position roles/responsibilities as part of a standalone entity (vs. part of a business unit, prior to the spin-off). It is often the case that benchmarking for SpinCo as a standalone entity will support an increase in pay for executive positions. For example, the top finance executive of a subsidiary is a very different role than CFO of a stand-alone public company. Some adjustments to base salaries and bonus opportunities may be made prior to and/or near the spin date, but should be made within the context of an overall compensation framework to the extent possible. The desired pay mix needs to be determined, with the appropriate emphasis on long-term (equity) incentives to ensure equity ownership build up and alignment with shareholders.

Annual Incentive Program

As with any company, the ongoing bonus program is designed so that funding is based on an appropriate mix of corporate, business unit and/or individual performance. The mix depends on the company’s emphasis on line of sight unit results or overall corporate team results. Performance metrics, whether top line, bottom line, or return based, should appropriately support the company’s strategy. Some investors may initially focus on EBIT/EBITDA or cash flow, yet ultimately determine that a balanced mix of metrics is desirable.

It is worth noting that for both short and long-term incentives, based on the tax code rules (IRC Sec. 162(m), the “performance based compensation” tax exemption for select executive officers), if a company gets an annual and long-term incentive plan approved prior to the Spin by the ParentCo board, and discloses such plan documents in any S1 filing, the company is exempt from IRC Section 162(m) rules for one year. Reapproval of such plan(s) by SpinCo shareholders is required prior to Sec. 162(m) transition relief expiring, and is also required under applicable stock exchange rules. Most companies, however, will still construct their plans to conform with “performance based compensation” rules and best in class industry/market practices.

Long-term Incentives

Key objectives of the Long-term Incentive (“LTI”) program for the SpinCo are to build executive/ employee stock ownership and to create excitement, engagement and alignment with shareholder value creation.

An important first step is to determine an overall equity pool to reserve for equity grants at the SpinCo, i.e., the amount of public stock outstanding that will be shared with employees as part of the compensation program. (This amount is generally under 10% of CSO, once initial IPO, has occurred and/or upon completion of the full spin; industry norms should dictate). At the initial IPO, or at full spin-off, it is common to grant a front loaded equity award to ‘jump start’ employee ownership in the new company. Some companies make a broad-based award to employees deeper in the organization, or beyond the executive group. Stock options and restricted stock are used for this type of grant, yet use of options (vs. full value awards) should be balanced with participation, share usage and cost considerations.

The core LTI framework for SpinCo should be designed to accomplish multiple objectives. Emphasis on equity programs helps to build shareholder alignment. Stock-based performance programs are strongly recommended. Not only do they reflect prevalent practice, but they are viewed favorably by large shareholders. Performance-based equity will also serve as a tool for the new leadership team to promote a focus on specific longer term performance results.

Like any LTI program, balance is important. While some specific industries may use more restricted stock than others (e.g., energy companies), most restricted stock is granted at lower levels in the organization, or for special retention/recognition grants. As a new entity, any new design presents an opportunity to assess long term performance goals related to business strategy and those being communicated to the marketplace. Such goals should likely be incorporated into the LTI program.

Vesting, form of payout and termination provisions are also important. The spin-off event is an opportunity for the new company to re-evaluate ParentCo practices. For example, SpinCo may choose to implement somewhat more stringent award termination provisions to support longer term employment of employees. To further align with best practice, companies should include CIC provisions that provide for outstanding award vesting only upon both completion of a CIC and termination of employment for good reason (i.e., a “double trigger”).

Severance provisions should be established as part of a formal severance (CIC/non-CIC) program or through severance agreements, or less common, as part of an employment agreement. These programs should be implemented after careful consideration of potential costs and benefits to the participant and to the company. Recognize that severance benefits are a sensitive issue for many investors. Tax gross-ups for any 280(g) CIC tax liabilities are no longer common and should not be included. Non-compete and non-solicitation provisions should be put in place for the new entity, as standalone policies or as part of LTI award agreements.

Governance Practices

Certain good governance practices that are commonly in place should be implemented, as they are in the best interests of SpinCo and shareholders and have come to be expected.

Stock Ownership guidelines are now very mainstream and expected by shareholders. They should apply to the newly formed executive group. In SpinCo, it may take some time to ramp up ownership in SpinCo stock, particularly if outstanding ParentCo equity awards were converted at spin using the shareholder approach. Keep in mind there should be a phase-in period before executives are held accountable and a ‘soft’ penalty my make sense, to help facilitate ownership, such as a required holding of 50% of net shares (vested or settled), until the guideline is met.

A Clawback Policy for any awards that were based on results impacted by an accounting restatement is a matter of good governance. A majority of companies today have one, with the ability for discretionary recoupment in the case of fraud or earnings restatement. Note that potential Dodd-Frank rules may mandate a “no fault” policy if finalized.

An Anti-Hedging Policy should be in place that prohibits executives from entering into any hedging transactions related to the company’s stock or trading any instrument related to the future price of the stock.

If Dodd-Frank rules are finalized as currently expected, companies may need to modify these provisions to comply with final rules, but on their own merit, these provisions should be put in place as a baseline.

Directors Compensation. The outside directors’ compensation program of SpinCo should ultimately reflect appropriate market norms for companies of similar size and industry, in terms of the amount of pay provided, the cash/equity mix, and overall structure of board and committee service pay. The design should consider the duties required of directors, as well as the company’s executive compensation philosophy. Initially however, the structure of SpinCo’s program will often resemble the ParentCo program.

The directors equity plan, if separate, follows the same rules as executive equity plans. The ParentCo board typically approves the SpinCo plan prior to the spin-off. Shareholders of SpinCo must reapprove the plan prior to IRC Sec. 162(m) transition relief running out, and also to comply with stock exchange listing requirements.

If any directors work on SpinCo activities prior to the spin-off, special equity compensation may be awarded, or pro-rated. If board leadership includes a non-executive chair or lead director, compensation will need to reflect the expected role, responsibilities and time commitment expected at that time.

4. Modification to ParentCo Compensation Programs Post-Spin

After the spin transaction, it is a good time for the remaining ParentCo to review its own compensation programs to ensure that they reflect the company’s new size and business focus. While not inclusive, the following program components may require review and/or potential modification:

Compensation Philosophy and Competitive Market. The company should assess who the appropriate peer companies are in terms of size, business mix, customers, geographic footprint, domestic vs international business, etc. It may be that the company maintains a market median pay philosophy, but that market position means something different now. If the company’s size is significantly smaller than before, pay levels will need to be monitored for alignment with the newly defined market over time.

Annual Incentive Program. The company’s annual incentive plan, in particular, may need revision so that the performance metrics reflect key drivers of the remaining entity and adjustments to the plan should reflect the new adjustments to the plan should reflect the new organization structure as it relates to any Business Unit or Division performance components. If the remaining business has slower growth prospects and lower margins, for example, the performance metrics may need to be redefined and the weightings reallocated. It may also be the case that there is more of a role for strategic goals as ParentCo also embarks on a new business strategy.

Long-term Incentive Plans. The company should reassess the role of various LTI vehicles at ParentCo. For example, in a low growth business, stock options are not the most effective long term incentive and the company may be better served by increasing the role of a three year LTIP. Conversely, the company may want to instill renewed enthusiasm around the ParentCo’s long term stock performance and growth potential. It may be an appropriate time to emphasize the role of equity. It is also a good time to reassess equity award participation as it relates to overall cost and/or share utilization, both domestically and internationally.

From a more technical standpoint, the Parent should review its current equity plans and share reserve, in light of the recapitalization. A spin-off event itself may not necessarily require revisions to plan documents, but it is an appropriate time to review documents to ensure that appropriate terms and provisions are included. It is also a good time to review compliance with IRC Section 162(m) and 409A.

The compensation related programs and provisions that need to be addressed and acted upon in a spin-off are comprehensive. It is important to the ongoing entities that both ParentCo and SpinCo business objectives are supported by appropriate pay design. At the same time, employee perspectives need to be considered as these transactions can present uncertainty. Planning should begin well in advance of any potential or planned transaction. A cross-functional team from HR, legal, finance and possibly outside advisors, should oversee the necessary action steps. This report can be used to help guide the process and compensation decisions that an organization will need to consider in a spin-off.

1 Source: www.spinoffresearch.com

The CAP 100 Company Research consists of 100 companies from 9 industries, selected to provide a broad representation of market practice among large U.S. public companies. In this report, CAP reviewed Pay Strategies, Annual Incentives, Long-Term Incentives, Perquisites, and Shareholder Friendly Provisions of these companies in order to gauge general market practices and trends.