Short-term, cash incentives continue to dominate the incentive-pay landscape at nonprofit/government organizations according to salary and compensation survey research released in May 2018 by WorldatWork in partnership with Vivient Consulting.

“U.S. nonprofit organizations continue to make significant use of short-term cash incentives to motivate and reward employees. Long-term incentive (LTI) use is still a little-used compensation element, but prevalence increased modestly in 2017 and may signal an emerging trend,” said Bonnie Schindler, partner and co-founder of Vivient Consulting.

Additional Key Findings from the WorldatWork-Vivient Survey

Nonprofit/Government Compensation Survey Results:

- Nonprofit and government organizations favor simplicity by offering a limited number of STI plans. Of the respondents, more than 75% reported having three or fewer STI plans in place.

- By far, the most common type of STI plan at nonprofit and government organizations continues to be an annual incentive plan (AIP). However, prevalence of AIPs dropped to 77% in 2017 from 86% in 2015

The compensation survey Incentive Pay Practices: Nonprofit/Government was conducted in December 2017 among WorldatWork members. The salary and pay survey is the third edition for nonprofit/government entities with the last report data released in 2015.

Short-term, cash incentives continue to dominate the incentive-pay landscape at private companies according to salary and compensation survey research released in May 2018 by WorldatWork in partnership with Vivient Consulting.

“Spending on short-term incentives (STIs) increased modestly at private companies from 2015 to 2017, which reflects the tight labor market and competition for talent,” said Bonnie Schindler, partner and co-founder of Vivient Consulting.

Additional Key Findings from the WorldatWork-Vivient Survey

Private Company Compensation Survey Results:

- Spending on STIs increased to 6% of operating profit at median, from 5% in prior years.

- The prevalence of exempt, salaried employees and nonexempt (salaried or hourly) employees included in annual incentive plans increased in 2017. The biggest jump occurred for nonexempt employees. Approximately two-thirds of nonexempt employees are eligible for annual incentives, up from half in 2015.

- The majority of respondents consider their annual incentive plans to be only moderately effective, with plan communication, the level of discretion, goal setting and the risk-reward trade-off noted as areas for improvement.

The compensation survey Incentive Pay Practices: Privately Held Companies was conducted in December 2017 among WorldatWork members. The salary and pay survey is the fifth edition of the compensation report produced for privately held companies with the last report data released in 2015.

Dan discusses compensation committee practices and how to take the process to the next level as well as new ideas for performance-based LTI.

Principal Bonnie Schindler discusses the compensation survey research conducted by Vivient and WorldatWork around incentive pay practices for private, non-profits and government entities.

The past year has been characterized by significant stock price volatility. Research indicates that the S&P 500 index has either gained 1% or more or lost 1% or more in a single day on 102 days during 2015. Individual stocks have experienced even higher volatility, with some industries (e.g., oil and gas, financial services) being hardest hit. This extreme variability in stock prices has continued through the period when most companies make annual grants of equity-based compensation to their directors, officers and employees. Since the overall stock price movement over this period has been down, many companies are finding that they need to grant more shares than they anticipated to deliver their targeted long-term incentive values to employees. In this CAPflash, we will lay out the nature of the issue and address alternative approaches that companies can use to respond to stock price decreases.

| Date | S&P 500 | S&P 500 Financials Sector | S&P 500 Energy Sector | S&P 500 Health Care Sector | ||||

| Value | ? vs. 8/15 | Value | ? vs. 8/15 | Value | ? vs. 8/15 | Value | ? vs. 8/15 | |

| 8/1/15 | $2,104 | – | $339 | – | $508 | – | $885 | – |

| 1/31/16 | $1,940 | -7.78% | $293 | -13.56% | $435 | -14.44% | $769 | -13.03% |

| 2/15/16 | $1,865 | -11.36% | $276 | -18.69% | $417 | -17.98% | $743 | -15.97% |

| 3/1/16 | $1,978 | -5.96% | $294 | -13.33% | $433 | -14.78% | $780 | -11.79% |

| 3/15/16 | $2,016 | -4.18% | $301 | -11.24% | $458 | -9.77% | $775 | -12.44% |

| 4/1/16 | $2,073 | -1.48% | $306 | -9.64% | $456 | -10.24% | $794 | -10.28% |

RECENT STOCK PRICES: A DOWNWARD TREND

In August 2015, around when many companies began their year-end compensation planning process, the S&P500 Index was at $2,104 and the S&P 500 Financials, Energy and Health Care sectors were at $339, $508 and $885, respectively. Scroll forward to January 31, 2016 and the S&P 500 Index was at $1,940 and the S&P 500 Financials, Energy and Health Care sectors were at $293, $435 and $769, respectively. The table below lays out the movements from August 1, 2015 into the current year, highlighting five common equity award dates.

While the overall indices moved significantly, the 25th percentile change through each of the above dates for companies in each of the above indices was as follows, indicating that for the lowest-performing one quarter of companies, stock prices fell by about 15% to 30%, or more, over this period.

| Date | S&P 500 | S&P 500 Financials | S&P 500 Energy | S&P 500 Health Care |

| 25th %ile ? vs. 8/15 | 25th %ile ? vs. 8/15 | 25th %ile ? vs. 8/15 | 25th %ile ? vs. 8/15 | |

| 8/1/15 | – | – | – | – |

| 1/31/16 | -20.21% | -21.14% | -35.26% | -22.72% |

| 2/15/16 | -25.24% | -29.25% | -45.40% | -25.25% |

| 3/1/16 | -18.29% | -22.02% | -37.35% | -21.86% |

| 3/15/16 | -17.22% | -19.37% | -27.40% | -22.76% |

| 4/1/16 | -14.78% | -18.10% | -31.67% | -19.32% |

MARKET NORMS FOR BURN RATE

CAP’s research indicates that burn rate (i.e., the number of shares granted during a given year divided by the weighted average number of common shares outstanding) among large public companies in the S&P 500 Index trends toward 1% of common shares outstanding when calculated excluding the factor of approximately 2X that ISS applies to full value awards to create equivalency with stock options. When the ISS conversion factor of approximately 2X is included, burn rate trends toward approximately 1.5% at median. On the lower end, burn rate of .5% or 1%, excluding or including the 2X conversion factor, respectively, is common. At the 75th percentile, burn rate of 2% to 4% is seen. This suggests that for a broad swath of public companies, ranging from $1 billion to $100 billion in revenues, burn rate in excess of 2% to 4% is difficult to sustain. Research on specific company peer groups could provide more refined comparisons, but this data gives the reader a general benchmark that applies across industries and size categories.

| Summary Statistics | Three-Year Average Burn Rate (including ISS Conversion Factor) | ||

| S&P Top 50 | S&P $5 B Cos. | S&P $1 B Cos. | |

| 75th Percentile | 2.13% | 2.55% | 3.82% |

| Median | 1.36% | 1.70% | 1.68% |

| 25th Percentile | 1.01% | 1.12% | 1.11% |

| Summary Statistics | Three-Year Average Burn Rate (excluding ISS Conversion Factor) | ||

| S&P Top 50 | S&P $5 B Cos. | S&P $1 B Cos. | |

| 75th Percentile | 1.03% | 1.32% | 1.88% |

| Median | 0.79% | 0.90% | 1.02% |

| 25th Percentile | 0.47% | 0.53% | 0.56% |

Note: S&P Top 50 reflects the 50 largest companies in the S&P 500 in terms of revenue with average trailing twelve month revenue of $108 billion. S&P $5 B Cos. reflects a 50 company subset of the S&P 500 with an average trailing twelve month revenue of $5 B. S&P $1 B Cos. reflects a 50 company subset of the S&P MidCap 400 with an average trailing twelve month revenue of $1 B.

IMPACT ON EQUITY GRANTS

Most companies make their annually equity grants based on a target dollar value for the long-term incentive award, rather than as a fixed number of shares. For example, a company may target a long-term incentive grant of $200,000 per year to a Vice President. For simplicity’s sake, let’s assume that the grant is made 100% in Restricted Share Units (RSUs). Most companies determine the number of shares to grant by dividing the target long-term incentive value by a stock price. Since companies are required to use the stock price on the date of grant for purposes of the disclosed value of equity grants, many companies use the stock price on the date of grant for converting award values into shares.

When the stock price declines significantly over a short period of time, there will be a significant increase in the number of shares required to deliver the target value. For example, let’s assume that the stock price was trading at $50.00 in September of 2015 when the company began their compensation planning and fell by 40% to $30.00 on March 1, 2016 when they make equity awards. In this situation, the number of shares required to deliver a $200,000 equity grant would increase by 67% from 4,000 shares to 6,667.

If the company is granting stock options, the share usage resulting from a decline in stock price is even more pronounced. Assuming a 3:1 ratio of options to RSUs, the grant required to deliver a $200,000 equity grant would increase from 12,000 options to 20,000 options.

Applied across the total employee population, this can create major concerns for the company with the potential to exhaust the reserve of shares available for grant under shareholder approved plans more quickly than anticipated. This will also increase the company’s annual share usage.

To the extent that equity plans reserves are exhausted and burn rates exceed industry norms, companies can run into difficulty when seeking shareholder approval of additional shares. If share usage is judged to be imprudent, or if shareholders see disconnects between pay and performance, particularly if facilitated by the equity plan, they are much less likely to support a request for new shares. The potential for perceived disconnects is heightened since higher burn rates typically occur when share prices are lower.

APPROACHES TO ADDRESS EQUITY GRANTS WHEN STOCK PRICE DECLINES

In our experience, companies address declining stock price in several different ways. The following are a few of the most common approaches:

Approach 1. Continue granting based on stock price at date of grant (i.e., do nothing)

In some cases, companies may feel that continuing to use their standard operating procedure for converting long-term incentive value into shares is the best approach. This could be because the company has been conservative in using shares in the past and has adequate shares available to cover multiple years of equity grants even with a significant stock price decline. The company may feel that a one year spike in their share usage will not raise significant concerns with shareholders or shareholder advisory firms. Another rationale that these companies may use for making grants as usual is that the value of any outstanding equity that executives hold will have fallen with the stock price. If the company reduces the value of equity grants as well, this may be a “double whammy” for long-term incentive participants. In our experience, Approach 1 can be untenable if the stock price falls by 30% or more.

- Advantages: Maintains target LTI award value for employees

- Disadvantages: Dilutive to shareholders; potential for “windfall” if stock price quickly recovers

Approach 2. Use an average stock price over a period of time to establish grants

This is a common approach companies use to mitigate the impact of short-term swings in stock price on the number of shares granted. Among companies that do not convert grant values into shares based on the stock price on the date of grant, the most common approach is to use an average stock price over a relatively short time period. We see a 20-trading day average most frequently. This approach avoids significant swings in the number of shares granted (up or down) based on stock price movement on the date of grant away from its near-term average. When companies have significant volatility over a sustained period of time, they may use a longer term average stock price (e.g., six months or one year) to mitigate the impact of volatility on grant size. The following chart lays out an illustration of this approach:

| Price Used | Target Value | Price | Shares | Acctng Value |

| Date of grant | $200,000 | $30.00 | 6,667 | $200,000 |

| 20-day average | $200,000 | $35.00 | 5,714 | $171,429 |

| 90-day average | $200,000 | $40.00 | 5,000 | $150,000 |

| 180-day average | $200,000 | $45.00 | 4,444 | $133,333 |

While using an average stock price helps manage the share usage when there is a stock decline, it will create disconnects between the target value of long-term incentives and the accounting value of the awards. Supplemental communication to employees is typically required to explain why the company thinks the average stock price methodology is a better estimate of value than the stock price on the date of grant. If the company uses this approach consistently over time, employees may recognize that the average price can be above or below the stock price on the date of grant.

- Advantages: Limits dilutive impact of stock price decrease

- Disadvantages: Potentially challenging to communicate to employees; disconnect between target LTI value and accounting value

Approach 3. Cap the run rate and pro rate grants accordingly

Some companies have committed to a maximum level of annual share usage or run rate. For example, a company may have committed to its shareholders or Compensation Committee that its annual run rate will not exceed 1.5% of common shares outstanding. If their stock price falls significantly, they may find that to deliver the target long-term incentive values under their program, they would need to grant 2.25% of common shares outstanding. In this situation, the company can pro rate all grants to keep the run rate at 1.5% of common shares outstanding. For example, if an executive’s target long-term incentive value was $200,000 and the stock price was $30.00, they would require 6,667 shares for this executive. Each grant would have to be multiplied by a factor of 1.5/2.25 or 2/3. In this case, the grant to the executive would be reduced from 6,667 shares to 4,444 shares and the accounting value of the award would be $133,333 instead of $200,000.

- Advantages: Limits dilutive impact of stock price decrease; simple; equitable treatment across employees

- Disadvantages: Reduces value of long-term incentive award to all employees

Approach 4. Limit participation in equity grants to conserve shares

Instead of making an across the board reduction in all equity grants, some companies will eliminate or significantly reduce long-term incentive awards for a portion of the population, while maintaining full awards for the remainder of the population. In practice, this often involves maintaining awards for senior executives where long-term incentives are viewed as most critical from a competitive perspective. For lower level long-term incentive participants, the company may limit grants to only those employees with performance that exceeds expectations or with critical skills. This approach may be acceptable if it is applied for one year, but may raise internal equity issues if extended beyond one year.

- Advantages: Limits dilutive impact of stock price decrease; targets awards at most critical employees

- Disadvantages: Potential strong negative response from excluded employees

Approach 5. Apply a discount to long-term incentive award guidelines

Another fairly simple way to address the issue of a stock price decline is to apply a discount to the long-term incentive award guidelines. Suppose that the stock price has fallen from $50 to $30 (or a 40% decline). In such a situation, the company would have to grant 67% more to maintain the LTI award target values. To mitigate the pressure that this will put on share usage, the company can apply a discount to the LTI target award value that partially adjusts for the impact of the stock price decline. For example, they could discount their LTI award guidelines by 25%. In this case, a $200,000 LTI award would be reduced to $150,000 and the grant would require 5,000 shares at a $30.00 stock price. This is more than the 4,000 shares that would have been required to deliver $200,000 at a $50.00 stock price, but is significantly less than the 6,667 shares required to deliver the full $200,000 at $30.00.

- Advantages: Limits dilutive impact of stock price decrease; simple; equitable treatment across employees

- Disadvantages: Reduces value of long-term incentive award to all employees

Approach 6. Use RSUs instead of stock options

To deliver a given long-term incentive award value, stock options require more shares than full value awards like RSUs or PSUs. Depending on the Black-Scholes value of stock options, the ratio of options to full value shares may be as low as 2:1 or as high as 5:1. For companies with equity plans that are not based on a fungible pool that treat options and full value shares the same, shifting the long-term incentive mix away from stock options towards full value shares can help ensure that equity grants will not exhaust the available pool.

For example, suppose a company has a mix of 50% stock options and 50% RSUs for its long-term incentive program. The company was planning on granting 1 million RSUs and 3 million stock options, but the stock price falls by 1/3 and now the company needs to grant 1.5 million RSUs and 4.5 million stock options. Unfortunately, their shareholder approved plan only has 5 million shares available for grant and the current 50%/50% LTI mix requires 6 million shares (1.5 million RSUs plus 4.5 million stock options). If they shift the mix from 50% RSUs / 50% stock options to 100% RSUs, the company will only need 3 million shares to deliver the target long-term incentive award value and they will not exhaust the share reserve.

- Advantages: Maintains target long-term incentive award value, potentially avoids exhausting share reserve, simple; equitable treatment across employees

- Disadvantages: Shareholders/Compensation Committee may prefer use of stock options to RSUs; shareholder advisors view RSUs as more dilutive than options on a per share basis

Approach 7. Use long-term cash instead of full value equity awards

Companies can conserve shares and reduce burn rate by replacing equity awards with cash. The most common approach is to grant long-term cash incentive awards instead of performance shares. Both types of award can be constructed with similar time frames, identical metrics and identical target values. But there are two significant differences. First, the ultimate value of performance shares will leverage up or down over the performance period in line with the value of the underlying shares. This exposes compensation realized by participants to additional volatility during periods when stock prices are uncertain. Cash awards will have more certainty and may therefore be valued more highly. Second, long-term cash awards are almost always settled in cash. Therefore, ancillary considerations, such as stock ownership guidelines, post-vesting holding periods, blackouts and insider trading policies are off the table.

In addition, long-term cash awards are not factored into burn rate calculations or into the estimates shareholders apply to the cost of equity plans. For example, ISS’ Equity Plan Scorecard does not value long-term cash, but would value outstanding performance shares. Similarly, long-term cash awards are not counted in calculations of overhang from equity plans or counted against equity plan share reserves, provided the awards are not denominated in share units settled in cash. Companies are required to book an accounting charge for the full cost of cash compensation, but effectively get a free pass on cash for other formulations of equity plan impact.

Awards of deferred cash designed to replace time-vested RSUs are seen less frequently, but could also be offered. The biggest decision involves whether to award fixed amount of cash for satisfying future service requirements or to provide either an interest component or some leverage tied to stock price performance.

- Advantages: Maintains target long-term incentive award value, potentially avoids exhausting share reserve, simple; equitable treatment across employees

- Disadvantages: Shareholders/Compensation Committee may prefer use of stock to cash to maintain alignment with shareholders

ADDITIONAL EQUITY COMPENSATION CONSIDERATIONS

In a time of severe stock price volatility, a company’s compensation program may be under pressure from multiple dimensions, beyond the current year’s equity grants:

- Reduced value of outstanding unvested full value shares: As the stock price declines, the value of any unvested equity held by employees will fall as well. This can reduce the value of outstanding equity as retention “handcuffs” and lowers the cost for competitors to buy executives out of their unvested equity. To the extent that all companies are affected equally by a stock price decline, this is not a major issue, but if the company’s stock price has declined more than the market overall, retention concerns will be heightened. If the company has a performance share plan, based on relative TSR and is underperforming on an absolute and relative basis, the retention issues will be even worse as the performance shares may be at risk of having no value

- Underwater stock options: A decline in stock price can reduce the intrinsic value of full value share awards, but as long as the stock price is above zero they still maintain some value. With stock options, the impact of a stock price decline can be more acute, as once the stock price falls below the exercise price the stock options no longer have any intrinsic value and employees may not place much value on the options at all.

- Economic uncertainty: To the extent that the stock price decline is driven by economic fundamentals (e.g., lower growth or lower profits), the company may have uncertainty about the likelihood of achieving its annual budget or long-term financial plan. This can further devalue the compensation program from the perspective of employees.

Unless the stock price decline is severe and sustained, it is uncommon for companies to cancel and replace underwater stock options or to make supplemental awards of full value shares to restore value to executives. However, when making compensation decisions in a year where the stock price has declined, it is useful to consider the context of employees’ total equity holdings and to err on the side of generosity for going forward equity grants to the extent possible.

CONCLUSIONS

Sudden stock price decreases can upset plans for annual equity grants by significantly straining the available share reserve and increasing the annual equity run rate. While there is no silver bullet approach that works for all companies, there are a number of alternative approaches that companies use to address stock price fluctuations. In choosing the approach that works best for your company, it is critical to determine the appropriate balance between the competing concerns of attracting and retaining employees with managing share dilution and protecting shareholder interests.

On April 21, 2016, the National Credit Union Administration (NCUA) issued joint proposed rules governing incentive compensation arrangements for the following agencies: Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (Board), Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. (FDIC), Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA), NCUA, and the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). The joint proposed rule is a revision to the proposed rule the agencies released five years ago on April 14, 2011 and is intended to implement section 956 of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (Dodd-Frank Act).

The new proposed rules are 279 pages long and have moved from the principles based guidance of the 2011 proposed rules to a more prescriptive approach that lays out specific incentive compensation practices that covered institutions are expected to comply with and explicitly prohibits certain practices. The agencies are soliciting comments between now and July 22, 2016. Covered financial companies are expected to comply with the proposed rule in the first calendar quarter that begins 540 days (18 months) after the final rule is published in the Federal Register. It will not apply to any incentive-based compensation plan with a performance period that begins before the compliance date.

Given the length of the proposal document, we will focus on summarizing the key provisions and provide some initial thoughts on its implications. It should be noted that much of what is in the new proposal builds on practices that many banks have already adopted as they have responded to regulatory input over the past five years. We will provide more comprehensive feedback as we develop a comment letter on the proposed rule.

Requirements and Prohibitions Applicable to All Covered Institutions

The new proposed rule is similar to the 2011 proposed rule in that it maintains the restrictions against establishing or maintaining incentive-based compensation arrangements that encourage inappropriate risk taking and by providing covered persons with excessive compensation, fees or benefits that could lead to material financial loss to the covered institution. A covered institution is one with at least $1 billion in assets.

The following provisions are consistent with the 2011 proposed rule:

- Excessive Compensation: Compensation, fees and benefits will be viewed as excessive when amounts paid are unreasonable or disproportionate to the services provided by a covered person, considering all factors, including:

- Combined value of all compensation, fees and benefits to a covered person;

- The compensation history of the covered person and other individuals with comparable expertise at the covered institution;

- The financial condition of the covered institution;

- Compensation at comparable institutions (specific criteria described in the proposal);

- For post-employment benefits, the potential cost and benefit to the covered institution;

- Any connection between the covered person and any fraudulent act or omission, breach of trust or fiduciary duty, or insider abuse with regard to the covered institution.

- Risk Balancing: An incentive-based compensation arrangement will be considered to encourage inappropriate risks that could lead to material financial loss to the covered institution, unless the arrangement:

- Appropriately balances risk and reward;

- Is compatible with effective risk management and controls; and

- Is supported by effective governance.

Key Addition: What is new in the proposed rule is that an incentive-based compensation arrangement would not be considered to appropriately balance risk and reward unless it:

- Includes financial and non-financial measures of performance;

- Is designed to let non-financial measures of performance override financial measures of performance, when appropriate; and

- Is subject to adjustment to reflect actual losses, inappropriate risks taken, compliance deficiencies, or other measures or aspects of financial and non-financial performance.

Board Oversight: Also, similar to the 2011 proposed rule, the new proposed rule requires that the Board of Directors:

- Conduct oversight of the covered institution’s incentive –based compensation program;

- Approve incentive-based compensation arrangements for senior executive officers, including amounts of awards, and at the time of vesting, payouts under such arrangements; and

- Approve material exceptions or adjustments to incentive-based compensation policies or arrangements for senior executive officers.

Covered Institution Categories

The proposed rules segment covered institutions into three main categories:

- Level 1: Greater than $250 billion assets

- Level 2: Greater than $50 billion assets, less than $250 billion assets

- Level 3: Greater than $1 billion assets less than $50 billion assets

The requirements of the proposed rule vary by type of institution with the more prescriptive aspects of the rule having the most impact on Level 1 and Level 2 covered institutions which due to their size and complexity are viewed as the most likely organizations to contribute to systemic risk. It should be noted that the Agencies have reserved the authority to require certain Level 3 institutions with assets between $10 billion and $50 billion to comply with the more rigorous requirements applicable to Level 1 and Level 2 organizations if they find that the complexity of operations or compensation practices are comparable to those of a Level 1 or Level 2 covered institution.

Risk Management and Controls

The risk management and controls required under the proposed rules are more extensive than prior guidance. Level 1 and Level 2 institutions would be required to have a risk management framework in place for their incentive based compensation programs that is independent of any lines of business and includes an independent compliance program to provide controls, testing, monitoring and training of the institution’s policies and procedures. In addition it would require covered institutions to:

- Provide individuals in control functions with appropriate authority to influence the risk-taking business areas they monitor and ensure that covered persons in control functions would be compensated independently from the areas they monitor; and

- Provide for independent monitoring of whether plans are appropriately risk balanced, events that relate to forfeiture or downward adjustments and compliance with the institution’s policies and procedures

While not as explicit in the 2011 rules this is another area where most large institutions have developed well defined risk management functions that independently oversee/monitor incentive compensation programs and participate in evaluating individual and plan compliance.

Governance

The proposed rule formally requires Level 1 and Level 2 institutions to establish an independent compensation committee (comprised of directors who are not members of management) to assist the Board of Directors in carrying out its responsibilities. It would be expected to obtain input from the institution’s audit and risk committees related to the effectiveness of the institution’s overall program and related processes. Management will be required to submit a written assessment of the effectiveness of the program, compliance and processes that are consistent with the risk profile of the covered institution. Separately, the compensation committee would also be required to annually obtain a similar written assessment from the audit or risk management function.

Level 1 and Level 2 institutions have generally integrated their processes for reviewing compensation programs and individual decision making with the risk (and audit) committee at least annually. Additionally compensation committees receive reports on a periodic basis from internal risk management. The rules provide a more detailed set of processes and documentation for these activities.

Disclosure and Record Keeping Requirements

The proposed rule requires all Level 1 and Level 2 covered institutions to create annually, and retain for seven years, documents that cover the following:

- Senior executives and significant risk-takers (listed by legal entity, job function, organizational hierarchy and line of business)

- Incentive-based compensation arrangements for senior executives and significant risk-takers, including percentage of incentive-based compensation deferred and the form of award

- Any forfeiture, downward adjustments or clawback reviews and decisions for senior executives and significant risk-takers

- Any material changes to the covered institution’s incentive-based compensation arrangements or policies

This record keeping requirement replaces an annual reporting requirement in the 2011 proposal. Based on our experience, in their interactions with regulators, most covered institutions have been required to develop and maintain extensive record keeping around their incentive compensation arrangements so the main new requirements are the specific content of the record keeping and the seven year retention period.

Covered Persons

The proposed rule describes specific employees that will be subject to the proposed rule labeled as senior executive officers and significant risk-takers. These categories are roughly equivalent to Category 1 and Category 2 employees under the 2011 proposed rules; however they have been expanded somewhat and the rules for defining significant risk-takers are somewhat more prescriptive.

- Senior Executive Officers:

- The following positions: President, Chief Executive Officer, Executive Chairman, Chief Operating Officer, Chief Financial Officer, Chief Investment Officer, Chief Legal Officer, Chief Lending Officer, Chief Risk Officer, Chief Compliance Officer, Chief Audit Executive, Chief Credit Officer, Chief Accounting Executive, or head of a major business line or control function

- Anyone performing the equivalent function to the above titles

- Significant Risk-Taker: There are two main tests to determine whether someone is a significant risk taker. If either test is met, the employee is a significant risk-taker

- Relative Compensation Test: For a Level 1 institution, are they among the 5 percent highest compensated covered persons; for a Level 2 institution are they among the 2 percent highest compensated covered persons

- Exposure Test: Does the covered person have the authority to commit more than 0.5% of the capital of the covered institution

- One-Third Threshold: A covered person will only be considered a significant risk-taker if 1/3 or more of their total compensation is incentive-based compensation

We suspect that many covered institutions will find that their current list of Category 2 employees has significant overlap with who will ultimately be considered significant risk-takers. However, organizations that have spent the past few years developing rigorous criteria for identifying Category 2 employees may find it frustrating to have to comply with a new set of criteria, particularly since the new criteria appear to be more sweeping and less tailored to the nature of specific institutions’ lines of business.

Deferral, Forfeiture, Downward Adjustment and Clawback Requirements

Deferral

The 2011 proposed guidance mandated covered institutions with more than $50 billion assets to require executive officers to defer at least 50% of incentive-based compensation for at least three years. The new rule expands the deferral requirement in several ways:

- Deferral Percentages: Amounts deferred have been modified to apply to senior executives and significant risk-takers with required deferral percentages by institution and employee designation. The table below summarizes the requirements by type of institution, type of incentive and class of executive:

|

Level / Incentive Type |

Senior Executive |

Significant Risk-Taker |

|

Level 1 – Short-term |

60% for at least four years |

50% for at least four years |

|

Level 1 – Long-term |

60% for at least two years |

50% for at least two years |

|

Level 2 – Short-term |

50% for at least three years |

40% for at least three years |

|

Level 2 – Long-term |

50% for at least one year |

40% for at least one year |

- Deferral Period: Deferrals cannot vest any faster than a pro rata basis over the full deferral period (i.e., for a Level 1 Senior Executive, the deferral of a short-term incentive cannot vest any faster that 25% per year over the four anniversaries of the award date; for a long term award deferral commences at the end of the performance period)

- Form of Deferral: Under the proposed rules, incentive based compensation will be deferred in cash and equity like instruments. While the rules do not propose specific percentages for each form they expect a degree of balance between the two. The rules are specific as to how much incentive based compensation can be deferred in the form of stock options.

- Stock Options: Under the proposed rules, stock options cannot represent more than 15% of the total incentive compensation used to meet the minimum required deferred compensation awarded for that period

- Acceleration of Deferrals: Level 1 and Level 2 covered institutions are prohibited from accelerating deferrals in any circumstances other than the death or disability of the covered person (i.e., no ability to accelerate upon other termination scenarios as is common today)

The more challenging aspects of the new requirements will be the mandatory deferral of both cash and equity in proportionate amounts, long-term performance plan payouts and the prohibition of the acceleration of deferrals. Companies may reconsider the amount of deferred compensation delivered in long-term performance plans if the new rules remain in place, as it will potentially diminish the value associated with plans due to the longer vesting period and increase the complexity of compensation programs. Many of these plans among Level 1 institutions have only recently been adopted and are well-received by long term investors. In addition, it is a fairly common practice to accelerate payouts of deferred compensation upon a termination of employment following a change in control or other termination scenarios (e.g., involuntary termination without cause or retirement). We suspect there will be additional commentary on this provision and that many institutions will begin to reexamine their practices as a result of the new rule.

Forfeiture and Downward Adjustment

Under the new proposed rules, the guidance has defined two new terms for practices that have been developed over the past few years as covered institutions have worked to comply with the 2011 proposed guidance:

- Forfeiture: A reduction of the amount of deferred incentive-based compensation that has been awarded but not yet vested.

- Downward Adjustment: A reduction of the incentive-based compensation not yet awarded to a covered person for a performance period that has already begun

Under the proposed rules all deferred incentive-based compensation will be subject to forfeiture and all not yet awarded incentive-based compensation will be subject to downward adjustment under the following circumstances:

- Poor financial performance attributable to a significant deviation from the covered institution’s risk parameters set forth in the covered institution’s policies and procedures;

- Inappropriate risk-taking, regardless of the impact on financial performance;

- Material risk management or control failures;

- Non-compliance with statutory, regulatory or supervisory standards resulting in enforcement or legal action brought by a federal or state regulator or agency, or a requirement that the covered institution report a restatement of a financial statement to correct a material error; and

- Other aspects of conduct or poor performance as defined by the covered institution

Under the proposal, the covered institution can exercise discretion in determining how much, if any, of an award will be impacted by the forfeiture or downward adjustment. However, in the proposal, there are specific factors that should be considered in making the determination, including the intent of the covered person, the covered person’s responsibility or awareness of the circumstances around the triggering event, actions that could have been taken to prevent the triggering event, the financial and reputational impact of the event, the cause of the events and any other relevant information related to the event, including past behavior of the covered person.

Based on our experiences with covered institutions, we expect this portion of the rule to be straightforward to comply with as most organizations have developed rigorous processes to cover forfeiture and downward adjustments over the past few years.

Clawback

The 2011 proposed guidance did not require clawbacks. Under the new rule, there will be a clawback provision covering any incentive compensation (cash and equity) for seven years from the time that the award vests. This would mean that some forms of deferred compensation could potentially be subject to clawback for more than ten years from the date that they were originally awarded. The clawback will apply to a current or former senior executive officer or significant risk-taker. While the time-frame for the new provision is long in duration, the triggering events for a clawback are described more narrowly than the events that would trigger a review for forfeiture or downward adjustment. Specifically, the triggering events for a clawback are defined as:

1. Misconduct that resulted in significant financial or reputational harm to the covered institution;

2. Fraud;

3. Intentional misrepresentation of information used to determine the senior executive officer’s or significant risk-taker’s incentive-based compensation.

This is one of the most significant changes included in the new proposal and is likely to result in significant comment. While it will be hard to argue with the triggering events, the time-frame for the clawback provision may create challenges in implementation and may create anxiety among covered employees.

Additional Prohibitions

While the bulk of the proposed rule is spent discussing the institutions covered, the individuals subject to the deferral requirements, the form of the deferral, forfeiture, downward adjustment and clawback requirements; there are some additional aspects of the rule that will be of interest to institutions and may have significant impact on compensation design.

Hedging

The proposed rule will prohibit covered institutions from purchasing hedging instruments on behalf of covered persons. As a practical matter, many financial institutions go further than this as they prohibit executives from engaging in hedging activities on their own behalf.

Maximum Incentive-Based Compensation Opportunity (also referred to as leverage)

Over the course of the last five years since the original guidance was provided, regulators have raised concerns with covered institutions over the degree of leverage in short-term and long-term incentive compensation arrangements. While many companies had incentive compensation arrangements with upside leverage of 200% of the target incentive opportunity when the 2011 rules were issued, most now have upside leverage of either 150% of target or 125% of target for their formulaic incentive-based compensation arrangements. The new proposed rule explicitly limits the upside leverage allowed for Level 1 and Level 2 institutions:

- Senior Executives: 125% of the target incentive opportunity

- Significant Risk-Takers: 150% of the target incentive opportunity

The professed intent is not to create a ceiling on incentive compensation but to constrain a plan feature that may contribute to inappropriate risk taking. However it will likely be viewed by institutions as weakening their ability to align pay with performance on the downside and the upside and as an uncompetitive feature when compared to other non-covered financial service firms or other companies.

Relative Performance Measures

Similar to the proposal on upside leverage in incentive plans, regulators have raised concerns over the use of relative performance measurement. While the proposed rule is described as a prohibition on relative performance, it is really just a prohibition on using relative performance measurement as the sole performance criteria in an incentive compensation plan. The majority of large financial institutions using relative performance measurement combine measures of absolute and relative performance in their plans. It is not clear what proportion of performance measures can be relative.

We expect that many organizations may continue to use the relative performance measure as a modifier or as some portion of a plan where the primary determinant of performance is based on the institution’s absolute performance.

Volume-Driven Incentive-Based Compensation

The proposed rules prohibit incentive compensation for Level 1 and Level 2 senior executive officers and significant risk-takers based on volume based performance measures without regard to the quality of the products sold or compliance with sound risk management. This restriction is more likely to have implications for incentive-compensation plans for significant risk-takers than for senior executive officers. In practice, most institutions have added assessments of compliance with risk management and credit quality to individual evaluations for incentive-based compensation so this may be more of a formality in terms of going forward compliance.

Conclusions

The new proposed rules are the culmination of five plus years of regulatory review of incentive-based compensation practices and follow a period of considerable interaction with covered institutions. A good portion of what is proposed is a codification of the discussions and exchanges that have occurred between financial institutions and their regulators. Some of the major new pieces of the rules, e.g., potentially larger group of covered individuals, increases to the required deferral percentages and vesting periods, required deferrals of long-term incentive compensation, the prohibition of acceleration of deferrals, and the lengthy and broader clawback requirement were likely not anticipated. We expect that the agencies will receive significant feedback on these points over the comment period. That said, we expect that much of the proposed rule particularly as it relates to governance and risk management, policies and procedures will be retained in the final rules, as they are generally consistent with guidelines that the large institutions have worked to implement over the past five years.

We believe Mr. Fink raises an important point on linking incentives to business strategy. A clearly communicated business strategy would help to avoid pitfalls that we see frequently today. These include incentives that are designed primarily to respond to pressure from proxy advisory firms, often driving a “one size – fits all” approach or encouraging short-term thinking.

“We are asking that every CEO lay out for shareholders each year a strategic framework for long-term value creation. Additionally, because boards have a critical role to play in strategic planning, we believe CEOs should explicitly affirm that their boards have reviewed those plans. BlackRock’s corporate governance team, in their engagement with companies, will be looking for this framework and board review.”

Larry Fink, BlackRock CEO

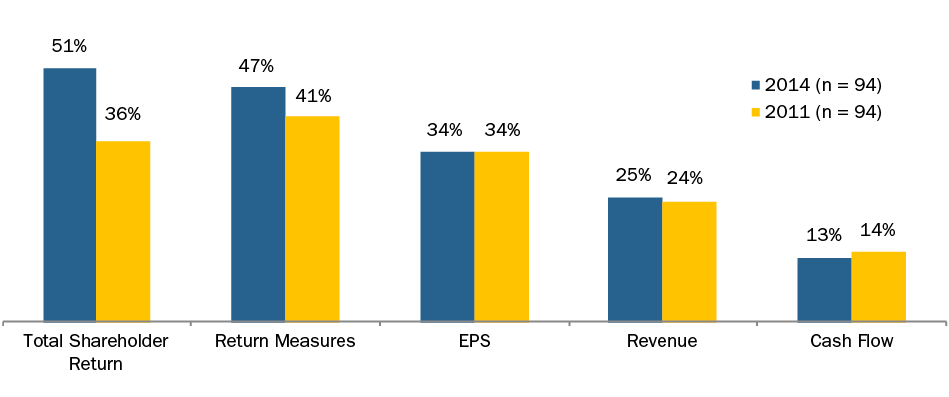

As highlighted by our articles Are You Rewarding Short-Termism? in The Corporate Board and Balancing pay for performance with shareholder alignment in the Ethical Boardroom, it is important that compensation, in particular long-term incentive compensation, links directly to the company’s strategy. We agree that providing shareholders with a voice on compensation programs through Say on Pay has been beneficial, but we have observed a chilling effect on creative compensation programs. Today most public companies are very reluctant to be an outlier on compensation. If we look at CAP’s sample of 100 large market cap companies, 51% use Total Shareholder Return (TSR) and 34% use EPS as metrics in their long-term incentive plans. Are these universal metrics appropriate in almost any situation? We question that premise. Why do so many companies have similar metrics when they have unique business strategies, operate in diverse industries and are positioned at different points in their lifecycle?

The good news is that we have observed modest increases in the use of return metrics, from 41% in 2011 to 47% in 2014 (e.g., return on assets, return on capital and return on equity). In several cases, activist investors have intervened to champion the adoption of return metrics. Traditional institutional investors with concerns over the effectiveness of corporate business strategies have also been vocal in encouraging companies to focus on returns. Both camps frequently push companies to move to adopt balanced metrics that encourage profitability in combination with growth as opposed to growth alone.

The chart below provides a snapshot of how long-term incentive plan metrics have evolved over time. Use of TSR has grown most since 2011, from 36% to 51% and this is after dramatic increases prior to 2011. We believe this is the direct outcome of the influence of proxy advisory firms, who have pushed hard on companies to incorporate relative TSR in their programs. The good news is that since 2011, the number of companies relying on a single metric has declined, with over 1/3 of companies using 3 or more metrics which may indicate they are tailoring plans more to their specific situation.

|

# of Metrics |

2011 |

2014 |

|

1 |

33% |

26% |

|

2 |

40% |

37% |

|

3 or More |

27% |

37% |

While EPS and TSR may make sense for many companies, companies should consider various factors when selecting measures, including:

- Is relative TSR the best answer for your company? We see it as an outcome-oriented metric that lacks a clear linkage to strategic priorities and is not well suited to driving behaviors that create shareholder value.

- Does over-reliance on TSR encourage risk-taking behaviors? Companies may make decisions that drive TSR in the short-term (e.g., share buybacks or higher dividends), rather than identifying better uses of capital that can lead to sustained long-term growth.

- Does an EPS metric create an incentive to buy back shares rather than re-investing for growth? Financial experts have mixed views on the utility of share buybacks. The jury is still out.

- Are the current time horizons for TSR performance optimal? Almost all plans measure TSR over 3 years. Why is a 3-year time frame the default for most companies? Since TSR is usually defined as a relative metric, eliminating the need to set goals in advance, should companies be evaluating longer timeframes that align with their business cycles?

- If relative TSR is your company’s metric, where are you in the cycle? Companies and boards need to ask and analyze whether relative TSR goals will pay out for sustained long-term stock price appreciation or for volatility in relative stock price performance. Companies and boards need to understand whether the stock is only recovering from earlier losses that occurred prior to the start of the performance period.

We don’t believe that either EPS or TSR are inherently poor metrics. In many cases, it makes sense for companies to incorporate these metrics into their overall incentive framework. However, it is critical to determine if these metrics are right for a particular company at a -particular time in its life cycle. Keep in mind that long-term incentives are the largest component of pay for many executives. As companies and boards design long-term incentives, they should consider the following questions:

- Does the compensation program support our strategy and do the metrics and goals align with our long-term business plan?

- Can we communicate clearly and succinctly how the program ties to our strategic framework for both shareholders and program participants?

- What behaviors, good or bad, could the design encourage? For example:

- Does it send clear signals throughout the organization on the strategic priorities?

- Is short-term upside emphasized at the expense of long-term sustained value?

- Do we encourage growth at the expense of returns that exceed our cost of capital?

- Does the program encourage excessive or inappropriate risk-taking?

- For metrics other than TSR, will achievement of goals lead to company and shareholder value creation?

- Are there alternative metrics, including strategic metrics (e.g., increase in market share, diversification of revenue, etc.) that might be better indicators of successful execution of the strategy?

Overall, we think Mr. Fink’s commentary on the importance of defining and communicating a company’s strategic framework for value creation serve shareholders well. His comments point to a fundamental principle of compensation design: incentive compensation should be used to reward the company’s success in achieving its strategy and creating long-term value for shareholders. The performance measures used to determine incentive compensation need to track progress on the strategy over the near term and over the long-term. We believe we will see a migration in this direction as long-term incentives evolve, companies continue to dialogue with their shareholders and perhaps as they enhance disclosure around their strategic framework as Mr. Fink suggests.