The Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act allows public company shareholders to vote on Named Executive Officer (NEO) compensation arrangements related to a merger and acquisition (M&A) transaction. This vote, required beginning in 2011, is also referred to as say on golden parachute. Similar to say on pay, these votes are advisory and non-binding. The say on golden parachute proposal must be in the same merger-related proxy in which shareholders are approving the deal. Companies are required to disclose all compensation that may be paid to the NEOs because of the transaction as well as the conditions under which they become payable.

Both parties of a deal are required to have a say on golden parachute proposal for shareholder approval. However, if a company’s executive compensation program has already been voted on by shareholders and the pay levels and program design are unchanged from the last shareholder vote, the company does not need to submit a say on golden parachute proposal; this typically applies to the surviving entity only.

Companies put golden parachutes in place for the most senior executives so they can continue to make decisions that are in the best interest of the company. These arrangements also encourage executives to stay through the close of the transaction. Over the past ten years, many companies have adopted shareholder-friendly practices, such as double-trigger vesting of equity (i.e., change-in-control occurs plus termination of employment) and removing excise tax gross-ups, given increased shareholder scrutiny and the advent of the say on pay vote.

Say on Golden Parachute Vote Outcome

In 2021, the majority of say on golden parachute proposals received shareholder support. Three-quarters of these proposals received 80% support or higher (average support is approximately 85%). Around one in ten proposals received less than 50% support.

Source: Proxy Insight

Proxy Advisors Perspectives

Proxy advisory firms, such as Institutional Shareholder Services (ISS) and Glass Lewis (GL), give investors a say on golden parachute vote recommendation. While these firms assess proposals on a case-by-case basis, they outline criteria used for the evaluation. ISS, for example, has multiple criterions used in their evaluation, but only note three that will most likely result in an against recommendation:

- Excise tax gross-ups

- Cash severance payment upon change-in-control without termination of employment (i.e., single-trigger)

- Single-trigger vesting of performance-based long-term incentives (LTI) with above target payout, unless there is a compelling rationale disclosed

Unlike ISS, Glass Lewis does not note any specific factors that could result in an against recommendation. Instead, they list criteria considered when evaluating the proposal including (but not limited to) the value (or magnitude) of payments, excise tax obligations, tenure and position of executives, use of single-trigger vesting, etc.

Shareholder Perspectives

CAP reviewed shareholder concerns from five recent acquisitions that failed their say on golden parachute proposal. Among these five companies, single-trigger vesting of LTI was the most common concern followed by excise tax gross-ups and large CEO retention bonuses. Shareholders are particularly concerned with single-trigger LTI vesting because executives could receive a windfall without termination of employment.

|

Company |

Industry |

ISS Rec’d |

GL Rec’d |

% Support |

Commonly Disclosed Shareholder Concerns |

|

ZAGG Inc |

Specialty Retail |

Against |

Against |

45% |

|

|

Extended Stay America, Inc. |

Lodging |

Against |

Against |

45% |

|

|

Covanta Holding Corp |

Waste Management |

Against |

Against |

41% |

|

|

Kansas City Southern |

Railroads |

Against |

For |

26% |

|

|

Five9 Inc |

Software – Application |

Against |

Against |

4% |

|

Source: Proxy Insight

While not commonly cited, some shareholders were critical of how the equity vests at time of termination. Specifically, some were critical of accelerated or continued vesting (i.e., no pro-ration) of time-based equity while others cited above target payouts of unvested performance plans. It is unlikely that these provisions alone would result in an against say on golden parachute vote. Regardless, a company should provide a rationale for pay decisions, particularly if providing one-time retention awards or when deviating from previously disclosed shareholder-friendly practices.

Implications of Failing Say on Golden Parachute

Say on golden parachute votes are one-time, advisory, and non-binding but companies should be aware that there could be consequences of failing for the surviving entity. Beginning with the 2021 proxy season, Glass Lewis stated that they may recommend against the next say on pay vote or compensation committee members of the acquirer if an excise tax gross-up is introduced. To-date, we have not seen many shareholders vote against say on pay proposals of the surviving entity. Given continued scrutiny, we anticipate companies will carefully weigh the pros and cons of implementing non-shareholder-friendly provisions at the time of the deal; for those that do, we would expect to see robust disclosure on the rationale.

2020 was a particularly robust year for initial public offerings (IPOs) and special purpose acquisition companies (SPACs). Many companies took advantage of favorable capital markets, and we saw much-anticipated IPOs such as Snowflake, DoorDash and Airbnb hit the public markets in 2020. Founders, employees, and investors unlocked significant value in these IPO events.

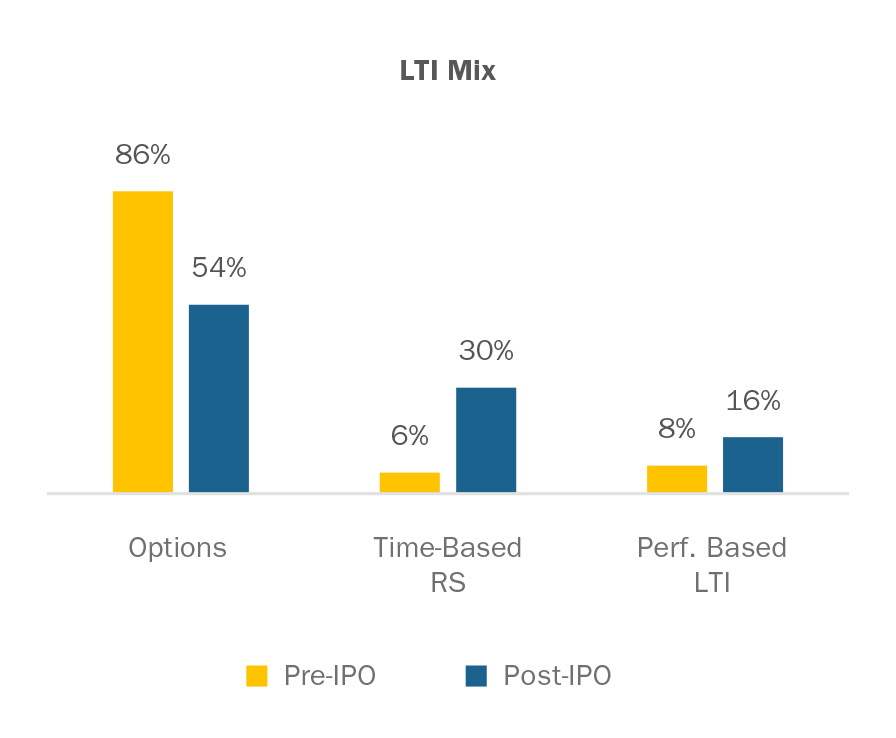

CAP’s review of technology company equity practices around IPO reveals several emerging compensation trends: a shift in equity award vehicles from stock options to restricted stock units (RSUs), increased use of double-trigger vesting for restricted stock, and large, company-friendly equity authorizations. Additionally, some companies implemented noteworthy founder compensation practices.

Pre-IPO Equity Grant Practices

CAP reviewed a sample of 20 high-profile, technology companies with IPOs in recent years to understand their equity practices leading up to the IPO.

List of companies:

| Airbnb | Fitbit | Palantir | Slack | Square |

| Asana | GoPro | Peloton | Snap | Uber |

| DoorDash | Grubhub | Snowflake | Unity Software | |

| Dropbox | Lyft | Roku | Sonos | Zoom Video |

Options are still predominant. For companies anticipating growth, options continue to be the favored equity award for a variety of reasons. For employees, there is no tax burden at vest, and the employee has control over the settlement of the award and associated taxation. If incentive stock options (“ISOs”) are used, the employee receives capital gains treatment upon disposition of shares, assuming the required holding period is met. Options are also favorable from the shareholder (often financial sponsors) perspective. Options align the interests of employees with their shareholders, as no award value is realized unless the company value appreciates. Typically, stock options are granted at-hire and allow employees to share in the value of the company as it grows and matures.

Increased use of RSUs with unique features. Some companies (such as Lyft, Uber, and Dropbox) shifted to granting more RSUs in the years leading up to IPO. In these cases, RSUs have double-trigger vesting, which requires both time-based service (typically four years) and event-based requirements (typically a qualifying capital event such as an IPO) be satisfied in order for the RSUs to vest.

Companies naturally shift from granting options to RSUs as they grow and mature. Reasons for this include changes in a company’s growth expectations post-IPO, the need to conserve shares, and a desire for differentiated equity grant programs as companies grow in size and complexity. However, as seen with recent IPOs, favoring RSUs could be attributed to the fact that award values are easier to understand and are somewhat protected, even if company valuations fluctuate between funding rounds. Companies also benefit, from an accounting perspective, with vesting being dependent on a qualifying capital event as no accounting charge is incurred until such event takes place.

Adopting double-trigger RSUs has potential downsides, though. These include mounting pressure to go public (as evidenced by media coverage of the long-delayed IPO of Airbnb), and a significant tax burden for employees whose equity vests upon IPO. Employees are exposed to the financial risk of being taxed on stock compensation that has since declined in value since IPO. Also, when employees leave the company before the IPO event, their unvested shares are forfeited. This may pose an issue for recruitment unless the IPO timeline is clear. For the company, event-based vesting triggers a major accounting expense, and the large number of shares being sold may temporarily impact the company’s share price.

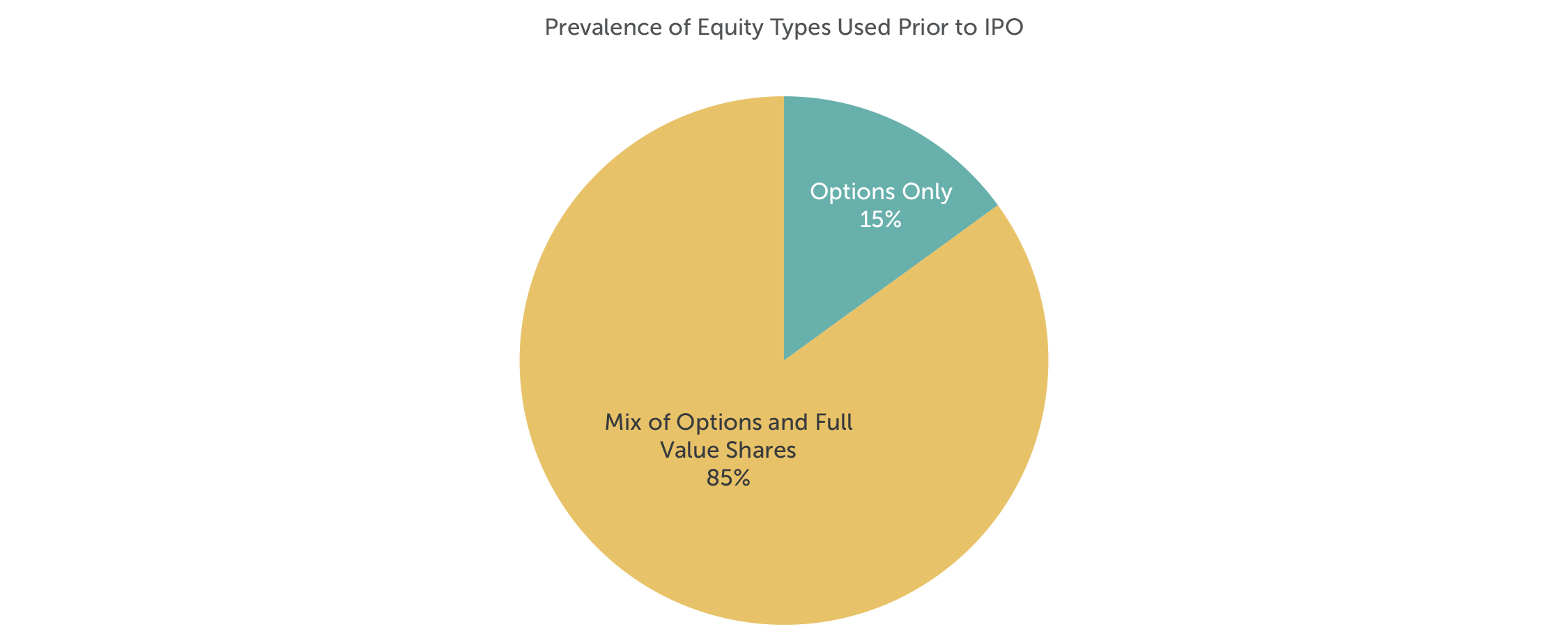

Note: No companies in the sample granted only full value shares prior to IPO.

Equity Authorization Pre- and At-IPO Practices

Before going public, companies often need to adopt multiple equity plans for incentive purposes. Not surprisingly, long time horizons and numerous funding rounds before IPO require companies to authorize additional equity share pools for compensation purposes. Private company investors are asked to approve incentives so that the company has enough “dry powder” to scale the executive team and grow its employee base. At median, equity overhang1 pre-IPO is 21.5% among the sample group.

In conjunction with the IPO, most companies (95% of companies in the sample), asked for an additional equity authorization. Median at-IPO overhang is 27.7% of common shares outstanding (CSO). In addition to the share request, companies often seek annual evergreen provisions (typically 5% of CSO per year) and liberal share recycling provisions.

Note: Pre-IPO and At-IPO equity overhang reflects the sample of 20 companies. Equity overhang for mature companies2 reflects sample (n=195) of S&P 1500 companies in the Information Technology sector, excluding companies that have gone public in the past three years.

Employee Stock Purchase Plans (ESPPs)

Many of the technology companies that went public implemented ESPPs in conjunction with their IPOs. ESPPs enable employees to purchase company stock, often at a discount, through payroll deductions. Most ESPPs are designed to be qualified plans under Internal Revenue Code Section 423, and from the standpoint of proxy advisory firms, such as ISS and Glass Lewis, are considered non-controversial. ESPPs are an appealing way for all employees to voluntarily acquire company shares after the IPO event. This is especially important as companies shift from granting equity to all employees to granting equity on a more selective basis (e.g., senior manager and up). An ESPP is an employee benefit that can be structured in ways (such as rollover provisions or extended offering periods) that make it an attractive recruiting and retention tool.

Founder Compensation

Every company has a different growth trajectory in its early years after formation. Founders typically must dilute personal ownership of the company in order to raise necessary capital. Companies in our study typically had multiple founders; however, not all founders contribute in the same way as the company evolves. Founders are often uniquely positioned and are key assets to their companies, which makes their retention crucial especially since finding a suitable replacement may be both difficult and expensive.

Founders who remain in executive roles after IPO have varied compensation packages depending on the specific circumstances. In some cases (Snap and Airbnb) founders reduced their base salaries to $1 post-IPO in exchange for significant equity grants in conjunction with the IPO. This is not typical as most founders maintain cash compensation (base salary and target bonuses) at market competitive levels.

With respect to equity compensation, some companies (including Airbnb and DoorDash) provided significant equity grants at or just prior to IPO. These grants often vest based on the achievement of performance criteria (e.g., stock price or market capitalization goals) and have long vesting periods that correspond with the magnitude of the award. Companies view these additional, often significant, equity grants to founders as necessary to incent continued service and focus, to maintain alignment with stockholder interests, and to mitigate the dilutive effects of public offerings on founder equity stakes.

Conclusion

Despite no “one-size-fits-all” approach to compensation, it is important to understand the various equity compensation tools available for companies preparing for an initial public offering. CAP’s review of recent technology IPOs highlights the latest trends in equity compensation needed to attract and retain skilled talent. Equally important is proactively and frequently communicating the value and mechanics of equity to participants for these awards to have maximum impact. Aligning pay philosophy with company culture and shareholder interests are important guiding principles to consider as companies design their equity incentive practices around IPO.

1 Overhang for IPO companies: Numerator = [Outstanding full value shares & options + shares available for grant + additional share requests] / Denominator = [Numerator + common shares outstanding as per the record date of the S-1 filing]

2 Overhang for Mature Companies: Numerator = [Outstanding full value shares & options + shares available for grant + additional share requests] / Denominator = [Diluted weighted average shares outstanding]

The COVID-19 pandemic dealt an unexpected blow that pushed a number of companies into bankruptcy. The impact of pandemic-related shutdowns was broad: Companies in a diverse range of industries – including retail, oil and gas, consumer goods, restaurants, and entertainment and recreation – filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection in the first half of 2020. While the number of filings has not yet reached the level seen in the 2008 financial crisis, the number of bankruptcies is expected to rise through the remainder of the year.

The 2020 surge in bankruptcies has been accompanied by heightened scrutiny of executive pay in restructuring situations. Bankruptcy filings are often preceded by announcements of executive retention and other short-term performance-based awards. These awards can draw criticism as excessive and even inappropriate given the impact of bankruptcy on shareholders and the broader employee population. However, 2020 is unique. While situations vary by industry, most agree that this flurry of bankruptcy filings is not the result of poor management but rather the inevitable impact of unprecedented and unforeseeable broad shutdowns across the country to contain the pandemic. The companies entering bankruptcy need continuity, stability, and motivated leadership. Carefully designed and communicated retention and performance awards can play an important role in keeping leadership in place and focused on moving the company through the restructuring process.

The Evolution of Prepaid Awards

Corporate bankruptcies cause a significant amount of uncertainty for executives and employees, who can be tempted to leave for more stable work situations with predictable, secure compensation streams. Poor company performance means that annual incentives are unlikely to pay out, and equity holdings lose almost all value. In situations where shareholders need to retain executives through the bankruptcy period, cash retention awards to critical members of management can be effective by providing compensation stability. These programs are often called Key Executive Retention Programs (KERPs).

Executive retention awards in bankruptcy situations today have a unique design: they are paid before the bankruptcy filing and are subject to clawback provisions. Clawback provisions are triggered if the executive terminates employment during a specified time period or is terminated for cause. In addition, some clawbacks are tied to performance goals not being achieved. If triggered, the clawback provisions require executives to pay back the after-tax award value. The fact that the awards are prepaid differentiates them from most other cash incentives and makes them the subject of criticism and misunderstanding.

The Evolution of Prepaid Executive Retention Awards in Bankruptcies

The unique design for executive retention awards emerged from changes to the U.S. bankruptcy code made through the Bankruptcy Abuse Prevention and Consumer Protection Act of 2005 (BAPCPA). Prior to BAPCPA, a large portion of executive compensation in bankruptcy situations was delivered through retention awards. Executive retention awards were typically paid out in a lump sum or through several payments based on the executive’s continued employment. Executive retention awards also had special status in the bankruptcy proceedings that ensured payment ahead of many other company obligations. As a result of the special status and lack of performance features, executive retention awards were not viewed favorably.

BAPCPA imposed stringent restrictions on awards to “insiders” implemented during the bankruptcy process that are based solely on retention and that lack performance features (“Insiders” are defined as directors, officers, individuals in control of the corporation, and relatives of such individuals). BAPCPA’s restrictions effectively stopped the use of executive retention awards once companies file for bankruptcy. Despite BAPCPA, executive retention awards eventually re-emerged – as prepaid awards subject to clawbacks. By paying the awards before the bankruptcy filing, companies can generally avoid the BAPCPA restrictions and avoid having the award subject to Bankruptcy Court approval.

Prevalent Executive and Employee Pay Practices during Bankruptcy

CAP analyzed the 8-K filings of a number of companies that entered bankruptcy in 2020. Based on this analysis, companies today often use a mix of compensation programs to retain and motivate executives and employees leading up to, and during, the bankruptcy process:

- Pre-filing, prepaid executive retention awards

- Performance-based Key Employee Incentive Plans (KEIPs)

- Employee retention and incentive programs

Pre-Filing, Prepaid Executive Retention Awards

A number of companies that filed for bankruptcy during 2020 announced prepaid retention awards for executives anywhere from days to months before the legal filing. The 8-K filings indicate that the prepaid retention awards are designed by the board with advice from compensation consultants, as well as bankruptcy and other advisors. Typical design parameters for executive retention bonus awards include:

|

Participation: |

CEO, other key executives and officers |

|

Objectives: |

Retain key employees before and during the bankruptcy proceedings |

|

Award Value: |

|

|

Form of Payment and Timing: |

Awards are made in cash, prepaid in a lump sum prior to the bankruptcy filing |

|

Clawback Provisions: |

Executives must repay the awards, net of taxes, if they 1) Terminate employment prior to the earlier of a specified period or the conclusion of the bankruptcy period, or 2) Are terminated by the company for cause |

|

Clawback Period: |

Most often one year |

While less common, some companies, including Chesapeake Energy and Ascena Retail Group, include base-level performance criteria in the clawback provisions to add a performance element to the prepaid retention awards. This improves the overall optics of such awards and helps avoid additional scrutiny during bankruptcy.

|

Select Pre-Filing Retention and Incentive Programs |

||||||

|

Company |

Revenue FY2019 ($000s) |

Industry |

Bankruptcy Date |

Program |

Award Term |

Description |

|

J.C. Penney |

$12,019 |

Retailing |

5/15/2020 |

Retention & Incentive |

0.6Y |

Adopted a prepaid cash compensation program equal to a portion of NEO annual target variable compensation; NEO awards ranged from $1M to $4.5M; clawbacks are tied 80% to continued employment through January 31, 2021, and 20% to milestone-based performance goals |

|

Retention |

1.6Y |

Accelerated the earned 2019 portion of three-year long-term incentive awards ($2.4M for NEOs); clawbacks are tied to continued employment through January 31, 2022 |

||||

|

Hertz Global Holdings |

$9,779 |

Transportation |

5/22/2020 |

Retention |

0.8Y |

Cash retention payments to 340 key employees at the director level and above ($16.2M in aggregate); NEO awards ranged from $190K to $700K; clawbacks tied to continued employment through March 31, 2021 |

|

Chesapeake Energy |

$8,408 |

Energy |

6/28/2020 |

Retention & Incentive |

1.0Y |

Executives: Prepaid 100% of NEO and designated VP target variable compensation ($25M in aggregate for 27 executives) based 50% on continued employment and 50% on the achievement of specified incentive metrics Employees (retention only): Converted annual incentive plan into a 12-month cash retention plan paid quarterly, subject to continued employment |

|

Ascena Retail Group |

$5,493 |

Retailing |

7/23/2020 |

Retention & Incentive |

0.5Y |

Executive and Employee Retention and Performance Awards: Six-month cash award for NEOs (NEO awards ranged from $600K to $1.1M), 3 other executives, and employees who are eligible for the company’s incentive programs based 50% on continued employment through Q4 2020 and 50% on performance; award amounts are based on a percentage of annual and long-term incentive targets Earned Performance-Based LTIP Awards: Accelerated earned 2018 and 2019 performance-based cash awards for all employees ($1.1M for 2 NEOs), subject to continued employment through August 1, 2020 for the 2018 award and August 3, 2021 for the 2019 award |

|

Whiting Petroleum |

$1,572 |

Energy |

4/1/2020 |

Retention |

1.0Y or Chapter 11 Exit |

NEO awards were prepaid and ranged from $1.1M-$6.4M; clawbacks are based on termination of employment before the earlier of March 30, 2021, or Chapter 11 exit; employees receive quarterly cash awards that in aggregate may not exceed that employee’s target annual and long-term incentive compensation |

|

GNC Holdings |

$1,446 |

Food, Beverage and Tobacco |

6/23/2020 |

Retention |

1.0Y |

Cash exit incentive awards for key employees (including executives) based 75% on the Company’s exit from bankruptcy and 25% on the 60th day following an emergence event that occurs on or prior to June 23, 2021. Prepaid NEO awards ranged from $300K to $2.2M |

|

Diamond Offshore Drilling |

$935 |

Energy |

4/26/2020 |

Retention |

1.0Y |

Past Executive Long-Term Cash Incentives: Payment of a portion of past three-year cash incentive awards was accelerated for retention; awards are subject to clawbacks based on termination of employment for one year; NEO payouts ranged from $140,208 to $1.75 million. Other Plans: The Company announced a Key Employee Incentive Plan, a Non-Executive Incentive Plan and a Key Employee Retention Plan, which are all subject to approval by the Bankruptcy Court |

Performance-Based Key Employee Incentive Plans (KEIPs)

After BAPCPA, KEIPs emerged to provide incentives to executives without running afoul of the bankruptcy code. KEIPs, which are approved during the bankruptcy process, are performance-based incentives that pay out in cash based on the achievement of financial and operational goals. The goals can be very short-term in nature, such as quarterly performance periods.

Typical design parameters for KEIPs include:

|

Participation: |

CEO, other key executives and officers (ultimately those designated as “insiders” in the bankruptcy proceeding) |

|

Objectives: |

Incentivize key executives before, but primarily during, the bankruptcy proceedings |

|

Award Value: |

|

|

Form of Payment and Timing: |

|

A current trend is to design and implement the KEIP prior to filing. This is especially true in pre-packaged bankruptcies where the financial reorganization of the company is prepared in advance in cooperation with its creditors. Having these programs in place with payouts contingent on performance improves continuity throughout the entire process, incentivizes the management team to perform, and meets the court’s requirement that any variable compensation to executives be performance based.

One recent example of a company announcing a KEIP before the bankruptcy filing is Diamond Offshore Drilling. The company announced a prepaid retention program for executives, as well as a KEIP, a non-executive incentive plan and an additional retention plan. All plans except for the prepaid executive retention program are subject to Bankruptcy Court approval, according to the 8-K. The KEIP, nonexecutive incentive plan and the additional retention plan replace past incentives – including requiring the forfeiture of past restricted stock unit awards and stock appreciation rights – and current incentives that would have been granted in 2020. The KEIP includes nine participants, including the senior executive team.

Employee Retention and Incentive Programs

Retention and incentive programs for employees are also used during the bankruptcy process. The use of employee programs depends on the company’s business needs and other factors, such as size and industry. Retention and incentive programs for non-executives typically replace the value of annual incentives and sometimes long-term incentives. Employee retention programs are cash-based and pay out at specific intervals, often quarterly given the uncertainties associated with companies in restructuring situations. The duration of employee retention programs often mirrors those for executives.

Severance programs, which provide compensation to individuals at termination, are also used in bankruptcy situations. When communicated broadly during bankruptcy, severance can be considered a retention program as it helps employees have some financial security and focus on their current jobs rather than finding new positions. Severance programs tend to be used more commonly for employees than executives because BAPCPA limits the value that can be delivered to “insiders.” However, a recent example of a severance program for executives came from Hertz Global Holdings, which announced amendments to its executive severance programs prior to its bankruptcy filing in May 2020. The severance programs, which were disclosed in the same 8-K filing as a prepaid key employee retention program, cover senior executives and vice presidents, and the payment multiple was reduced to 1X salary and bonus from 1.5X.

Conclusion

Executive compensation programs implemented in conjunction with a bankruptcy should be carefully designed and reviewed with outside advisors to ensure that the company is complying with bankruptcy code. Companies should carefully review the value of executive awards to ensure that they are reasonable while also in line with competitive practices and past incentive opportunities. Executive award amounts should be considered in the context of employee awards and the company’s overall financial situation to ensure fairness and avoid the appearance of excess. Lastly, companies should carefully communicate the rationale for executive awards and what the company is doing for employees in the 8-K current report or other announcement. Clear communication up front can help head off later public relations and optics headaches.

Imagine this scenario: Company A acquires Company B. The acquisition is transformational for Company A since Company B’s products are complementary, the geographic footprint of the combined company is larger and substantial synergies may be realized after the deal closes. The transaction is not without risk however, since Company A is funding the purchase by issuing several billion dollars of long-term debt, greatly increasing the leverage on the balance sheet.

The due diligence is well underway. The transaction is expected to receive shareholder approval and close shortly. What are the compensation implications? What should Company A’s HR staff and Compensation Committee focus on? What are the most important issues at this critical juncture?

Due Diligence

The due diligence process provides an opportunity to develop a high-level understanding of the target company’s organization structure, employees and compensation and benefit programs. The purpose is to identify potential liabilities that might crater the deal or require an adjustment to the purchase price. Key areas of focus include developing an understanding of contractual rights, the value of severance plans and change in control agreements, retiree benefits and any unusual plans or practices.

An important aspect of the due diligence process from an HR perspective is to understand the retention hooks that will remain in place following the acquisition. An understanding of retention allows the HR team to estimate the potential cost of additional incentives, equity and severance benefits needed to retain key talent after the transaction closes, as well as to right-size the organization, if appropriate. As part of this review, the HR team commonly prepares a side-by-side comparison of the compensation and benefit programs of the two companies.

New Organization Structure

The impact of the newly acquired business on the acquiring company’s organization is an important question to answer early in the process. One fundamental issue is whether the acquired business and associated products and services will be merged into existing business units or managed as a separate, stand-alone business unit.

Retention of key employees with customer relationships, product knowledge and a grasp of business fundamentals is a critical priority for the new organization. In many cases, headcount reductions are likely to be extensive. Identifying potential replacements for critical roles is also very important if retention efforts are unsuccessful.

Retention Incentives

Many organizations reserve a pool to fund merger-related retention incentives. Examples disclosed in public filings related to large acquisitions appear in Table 1. These examples reflect mergers closing between 1/1/2015 and 12/31/2016, with transaction values of $10 billion or more (per Capital IQ).

As these examples illustrate, substantial sums are allocated to retaining employees in large transactions. While there is considerable variation, depending on the specific circumstances of each situation, the approaches to retention incentives that we see most frequently are summarized below:

|

Participation: |

Selective; Offered to key employees |

|

Size of Award: |

50% to 100% of regular performance-based annual incentive |

|

Payout Schedule: |

1 installment for retention periods of 1 year or less; 2 installments for retentions periods of 12-24 months |

|

Form of Payment: |

Cash; Stock is used less frequently |

|

Vesting: |

Payment is made if company initiates early termination; Payment is forfeited if employee resigns voluntarily |

Proxy advisory firm support for these arrangements has been mixed. ISS recommended “For” the advisory vote on golden parachutes in 11 of 18 cases, while 7 companies received an “Against” recommendation. Despite ISS’ recommendations, 15 of 18 companies received majority support for their golden parachute votes, with only 3 companies failing to win shareholder support.

Table 1

Select Examples of Merger-Related Retention Compensation

|

Merger (Target & Acquirer) |

Transaction Value |

# of Employees at Target |

Merger-Related Retention Compensation |

ISS Recommendation / Results for Advisory Vote on Golden Parachute |

|

Allergan & Actavis |

$72.9B |

10,500 |

$20M pool for cash retention bonuses to Allergan employees (excluding executive officers) |

For / Pass |

|

Cameron Int’l & Schlumberger |

$16.6B |

23,000 |

$50M pool for retention bonuses and other awards to Cameron employees and executives |

Against / Pass |

|

CareFusion & Becton Dickinson |

$13.8B |

16,000 |

$25M pool for cash retention bonuses to CareFusion employees |

For / Pass |

|

Charter & Time Warner Cable |

$78.7B |

56,430 |

2017 retention equity grants for approx. 1,900 employees totaling $148M

2015 supplemental bonus for approx. 14,000 employees to be paid on July 1, 2016

|

Against / Pass |

|

Chubb & ACE |

$31.6B |

10,200 |

$100M pool for short-term cash and long-term equity retention awards to Chubb employees (excluding CEO) |

Against / Fail |

|

Covidien & Medtronic |

$48.1B |

39,500 |

$20M pool for cash retention bonuses to Covidien employees (excluding executives) 2 Covidien executives joined Medtronic and received one-time new-hire stock compensation totaling $6.4M

|

For / Pass |

|

DIRECTV & AT&T |

$70.3B |

30,925 |

$190M pool for cash retention bonuses to DTV Employees (excl. CEO and CEO’s direct reports) |

For / Pass |

|

IMS Health & Quintiles |

$13.5B |

15,000 |

Quintiles CEO (Vice Chairman of the surviving entity) received retention awards, payment of which was subject to his continued employment on specified vesting dates:

One NEO also received a retention award of $750K in RSUs that vest ratably over three years |

For / Pass |

|

Jarden & Newell |

$19.0B |

40,000 |

President of Newell Brands, who had previously announced his intention to retire at the end of 2015, received $1.4M in RSUs and $3.0M in PBRSUs to recognize his expanded role following the merger and to promote his retention

|

Against / Fail |

|

Kraft & Heinz |

$55.0B |

22,100 |

Kraft COO received a $4M retention bonus |

For / Pass |

|

LinkedIn & Microsoft |

$29.3B |

10,113 |

LinkedIn CEO received a retention award of $7M in RSUs, which vest one year after the close of the merger |

Against / Pass |

|

Safeway & Albertsons |

$12.4B |

137,000 |

Certain key Safeway employees (excluding CEO), received cash retention bonuses ranging from 50-75% of salary

|

For / Pass |

|

Starwood & Marriott |

$15.8B |

188,000 |

$40M pool for retention awards to Starwood employees Starwood CFO received a retention award of $200K, which vested 60 days after the close of the merger or upon termination without cause or resignation for good reason |

For / Pass |

|

Tyco & Johnson Controls |

$16.8B |

57,000 |

JCI merger retention program provided for retention awards to be made to executive officers in the form of time-based RSUs, which generally vest after 3 years with automatic acceleration upon a qualifying termination

Four Tyco executives received cash retention awards with a total value of $2.1M under the Tyco retention and recognition program, which was adopted in connection with the merger |

Against / Fail |

Sources: Transaction data from S&P Capital IQ; compensation data from target company merger proxy and/or combined company proxy; voting data from ISS

Post-Merger Integration Incentives

Some companies also introduce special incentive plans tied to the capture of synergies post-merger. Six examples appear in Table 2. Post-merger performance can be measured in different ways. After large acquisitions, teams representing all major functions – marketing, sales, supply chain, R&D, HR, etc. – are created. Team members are tasked with achieving integration goals in a timely manner, often requiring significant investments of time and effort. Additional bonuses, either discretionary or performance-based, are frequently provided.

For performance-based incentives, one approach is to measure the specific cost savings realized following the merger. A second approach involves assessing the overall financial performance of the combined company. We believe the second approach is generally more effective since such a program answers fundamental questions: Did the deal achieve the promised ROI? Can we call it a success for shareholders and other stakeholders?

Table 2

Select Examples of Post-Merger Incentive Compensation

|

Merger (Target & Acquirer) |

Transaction Value |

# of Employees at Target |

Post-Merger Incentive Compensation |

ISS Recommendation / Result for Say on Pay Vote |

|

Allergan & Actavis |

$72.9B |

10,500 |

Members of the senior management team received cash-based “Transformation Incentive Awards”:

|

Against / Pass |

|

Chubb & ACE |

$31.6B |

10,200 |

Certain ACE employees (incl. NEOs) received a supplemental award of PBRS:

|

For / Pass |

|

Lorillard & Reynolds American |

$28.5B |

2,900 |

All full-time employees (excluding the CEO) received one-time “Game Changer” cash incentive awards

|

For / Pass |

|

Starwood & Marriott |

$15.8B |

188,000 |

All NEOs except for the Executive Chairman received “Business Integration” PSUs

|

For / Pass |

|

Kraft & Heinz |

$55.0B |

22,100 |

Kraft COO received a special incentive bonus with a target value of $10M and a minimum guaranteed value of $7M

|

For / Pass |

Sources: Transaction data from S&P Capital IQ; compensation data from combined company proxy; voting data from ISS

Integrating Compensation Programs

The merger agreement often provides that compensation and benefits will be maintained at existing levels for a defined period, typically one year but sometimes as long as two years. This allows for some time to assess the compensation and benefit programs at the newly acquired business and develop an action plan. In most cases, employees of the acquired company are added into the programs of the acquiring company. But in some cases, it may be appropriate to merge the programs by selecting the best features of each.

Action steps are situational. The specific facts and circumstances of the combined company will dictate the optimal compensation program design decisions. While each company will come to its own conclusions, here are some suggested areas of focus:

- Develop Employee/Executive Roster: Assemble a tally of headcounts and compensation levels by business unit, level and geographic location. Understand the population and markets that you are dealing with. Recognize that roadblocks created by different HRIS systems may make this more difficult than expected.

- Address Titling Conventions: Determine the extent to which job titles are consistent. Assess whether span of responsibilities associated with different titles (i.e., Manager, Director, Senior Director, etc.) are similar. If inequities exist, develop an action plan to achieve uniformity.

- Develop Integrated Salary Structure(s): Depending on current practices, this may involve traditional salary ranges or salary bands. It can be supported by job matching to survey data, or other job evaluation systems. Multiple structures in different geographies may be required. This is a critical step to achieve internal equity, but it also requires time to analyze and implement, as well as input from the HR generalists in the business units.

- Expand Participation in Annual Incentives: The place to start is to make a side-by-side comparison of the annual incentive plans of the acquired and acquiring companies. There are a number of fundamental questions to address:

- Do both companies use performance against budget as the basis for annual incentives?

- Are the award opportunities consistent at target? At threshold? At maximum?

- Should award opportunities of newly acquired participants be adjusted or grandfathered?

- What are the performance metrics? Are they similar or different? What makes sense going forward?

- How about the performance scales? Are the performance ranges and payout percentages similar?

Well thought out decisions on each of these points will help create an annual incentive plan that supports business success and creates a bridge between the legacy populations.

- Expand Participation in Long-Term Incentives and Equity: Including newly acquired personnel in the long-term incentive and equity programs requires a similar decision-making process. Since long-term compensation is a significant component of pay at the director level and above at most companies, it is important to size it correctly. Companies should also project the impact of expanded participation on share usage and make sure that the existing plans can fund awards.

Frequently the acquiring company assumes the equity plan sponsored by the acquired company. The shares in the plan are converted to reflect the equity of the combined company. This provides another source of shares. However, these shares can only be used for employees of the acquired company unless shareholder approval is obtained. Depending on the size of the two plans and the share usage, this may be a worthwhile step to take.

Conclusion

A large acquisition raises a host of compensation and benefit issues. Working through the process of analyzing and integrating compensation programs frequently requires several years. Decisions made after a large acquisition have important implications for talent retention, performance of the combined company and the board of directors’ ultimate judgment on whether the transaction was successful. The HR team plays an important role in the process, beginning with due diligence and continuing through the integration process.

CAP consultants have supported many large transactions. Any of our partners would be happy to talk through the implications of an acquisition on incentives and other HR issues.

Spin-offs have been in the news for several years. Fully 60 spin-off transactions occurred in 2014, followed by another 40 spin-offs in 2015, with 13 involving S&P 500 companies.1 Spin-off activity continued to be newsworthy in 2016 with major spin-offs completed by Alcoa, Danaher, Emerson Electric, Johnson Controls, and Xerox. Spin-off activity will continue into 2017 with a number of pending transactions including major companies like Ashland, Biogen, Hilton Worldwide, and MetLife. The need to create shareholder value during a period marked by low returns from most asset classes is driving the spin-off activity. In some cases, activist shareholders have pushed companies to create value by breaking businesses into their component parts. When a business undergoes a spin-off, the human resource and executive compensation implications for executives at both the Parent Company (ParentCo) and the Spin-off Company (SpinCo) are very significant.

We have advised many companies as they worked through the spin-off process and we want to share some of what we have learned. As a starting point, we have identified four critical work streams for executive compensation in a spin-off:

- Establishing Transitional Compensation Arrangements (e.g., near-term retention plans)

- Understanding and/or Modifying Outstanding Compensation Arrangements (e.g., outstanding equity awards, severance and change in control agreements, benefit plans, etc.)

- Developing Going Forward Compensation Programs for SpinCo, equivalent in many ways to standing up a newly public company in an IPO

- Modifying Compensation Programs for ParentCo, as necessary to reflect new business focus and business scale

1. Establishing Transitional Compensation Arrangements

After deciding that a portion of the business is going to be spun-off, one of the first compensation decisions that needs to be addressed is how to structure incentive compensation programs for the company in the year of the spin-off. How complex this step is will depend on the timing of the spin-off in the fiscal year and the nature of the company’s annual and long-term incentive plans. A general principle is that if the spin-off has already been announced at the time design decisions are being made, SpinCo incentive compensation should be based primarily on SpinCo performance to provide better line-of-sight for SpinCo employees and to facilitate the transition.

Annual Incentive Plans

If the upcoming spin-off is a known event at the time that the annual incentive award is made, the transitional incentive plan can be simplified by ensuring that the annual incentive for SpinCo executives is tied 100% to SpinCo performance for the entire fiscal year. In this case, SpinCo executives will be paid an annual incentive based on SpinCo’s performance early in the fiscal year following the spin-off.

In some cases, the annual incentive award may already have been granted prior to the announcement of the spin-off. In such a situation, it is likely that the incentive plan for SpinCo employees will be based on a combination of ParentCo and SpinCo performance up to the time of the spin-off and then on SpinCo performance for the remainder of the year. This may require the company to establish SpinCo specific performance goals for the “stub period” from the completion of the spin-off to the end of the fiscal year. The performance measures for the “stub period” are typically the same performance measures used to assess SpinCo performance for the portion of the fiscal year prior to the completion of the spin-off.

Long-term Incentive Plans

Similar to the short-term incentive, if the company knows that the spin-off is going to take place during the fiscal year, there are design decisions that can help to facilitate transitioning the long-term incentive awards. For any performance-based awards (e.g., performance shares/units/cash), SpinCo employees should be granted awards that are based on multi-year performance objectives for the SpinCo. In some cases, companies will avoid making performance-based awards to SpinCo employees in the year of the transition because of the challenges in maintaining a consistent performance measurement approach before and after the spin-off.

If the spin-off is not a known event at the time that performance awards are made, there may be challenges in converting ParentCo performance awards into SpinCo performance awards at the time of the spin-off. In these cases, some companies will truncate the payout based on the ParentCo performance to date, at spin, and establish SpinCo goals for the remainder of the overall performance period. We will address this issue in greater detail in the next section on the treatment of outstanding awards following the spin-off.

Special Transition Compensation Programs

Most SpinCo employees are likely to view the spin-off as a positive event. Staff positions (e.g., finance, legal, human resources, etc.) will often have enhanced roles and responsibilities at the new company, given the stand-alone nature of the business. Line positions (e.g., business unit executives and staff) often feel that the spin-off provides them with a greater ability to impact business performance.

On the other hand, announcement of a spin-off creates uncertainty about the future prospects of the business. In addition, the SpinCo is a potential acquisition target, with the business potentially being sold rather than spun-off to shareholders. In many cases, it makes sense to review the severance protection in place for SpinCo staff in advance of announcing the spin-off. If there is a real chance that the business may be sold, enhanced severance protection may be needed to ensure that staff positions do not “jump ship”.

There may also be employee retention concerns at the ParentCo. While the spin-off is generally a positive event for SpinCo employees, spin-offs can create concerns for ParentCo employees. For ParentCo employees, a spin-off means working for a smaller company in the future, with a less complex and potentially less interesting job. In addition, the spin-off transaction will create additional work for all corporate staff positions as they set up the newly public company and continue to do their “day job”. For select ParentCo employees, a near-term retention bonus or short-term stock retention grant may provide recognition for their additional workload and focused efforts on preparing for a successful transaction, and help to keep them engaged in a stressful working environment. To the extent that certain corporate staff positions will no longer be needed following the spin-off, there may also be a need for enhanced severance for corporate staff.

2. Understanding and/or Modifying Outstanding Compensation Arrangements

As the company approaches the spin-off, a key compensation issue is how to adjust outstanding compensation arrangements to recognize that one company is breaking up into two companies. Decisions need to be made about what will happen to the company’s long-term incentive plans, as well as retirement plans and deferred compensation plans. For purposes of this discussion, we will focus on long-term incentive plans, as it is an area that is particularly critical for executive compensation.

The treatment of outstanding long-term incentives (particularly equity incentives), can be complex following a spin-off. There are several steps that need to be taken to transition awards, including review of the following:

- What provisions are specified in the equity plan and equity award agreements?

- Should the Committee apply discretion to modify the treatment of employees’ awards based on the circumstances of the transaction?

- What is the preferred approach for converting ParentCo equity (i.e., ParentCo post-spin and SpinCo equity)?

- What will be the timing of the conversion of equity?

Existing Equity Plan and Award Agreements

The first step in reviewing outstanding equity is to understand the treatment that the company’s equity plan and the individual award agreements prescribe for outstanding equity awards. A key issue to understand is what will happen to the awards held by employees of SpinCo. In many cases, the spin-off constitutes a termination of employment and, under ParentCo’s plans, unvested awards are forfeited at the spin-off.

It is important to understand the extent to which the prescribed approach impacts the bottom line of both entities. It is also important to work with internal and external counsel to ensure that there is a common understanding of the contractual rights of employees under the equity plan and award agreements.

Another key issue is whether the plan provides for the conversion of outstanding awards in a spin-off transaction. The plan document will likely include a section addressing a change in capital structure and transactions like a spin-off. In most cases, the Committee is required to convert vested awards to preserve value, but is afforded significant latitude in determining the details of the conversion.

Exercise of Compensation Committee Discretion

In our experience, most Compensation Committees do not want SpinCo employees to forfeit outstanding unvested equity as a result of a spin-off transaction. Forfeiture of previously awarded equity could have a serious impact on morale. One way to address this is to accelerate vesting in ParentCo equity or to provide for continued vesting post-spin. Alternatively, if the ParentCo’s Compensation Committee does not take action to keep SpinCo’s employees whole, then SpinCo’s Compensation Committee may need to take action following the spin-off. But it is important to keep in mind that each situation is different. If outstanding awards are underwater, the spin-off may be an opportunity to eliminate overhang on the stock.

Approaches for Conversion of ParentCo Equity

There are several approaches that are used in practice when addressing how to treat outstanding equity upon a spin-off. The following table provides an overview of the alternative approaches:

|

Approach |

Description |

|

Employee |

Employee awards are converted to equity in the company where they are employed. The participants of the equity plan who remain employed by ParentCo retain adjusted ParentCo equity awards. The equity plan participants who are employed by SpinCo receive converted SpinCo equity awards with same terms and conditions |

|

Shareholder |

Employees are treated like shareholders. Regardless of where the participant is employed following spin-off, outstanding awards of all equity plan participants are converted into both ParentCo and SpinCo equity at the same conversion ratio as shareholders, with the same terms and conditions as the original awards |

|

Hybrid |

A combination of the “Employment” and “Shareholder” approaches based on any of the following: (i) when the equity award was granted, (ii) where the equity holder is employed post-spin, (iii) when the equity award will vest, and/or (iv) the type of equity held at spin-off |

|

Adjustment Only, No Conversion Approach |

All employees retain adjusted ParentCo equity with same terms and conditions. Continued employment with SpinCo is treated as employment with ParentCo, for purposes of continued award vesting |

While several approaches to conversion are used in practice, the Employee approach is the most consistent with the goal of aligning the executives of the company with the shareholders of the entity they support following the spin-off. Other approaches (e.g., shareholder) may attempt to recognize the efforts of employees, prior to the spin, given that such efforts contribute to the future business success of both entities, post spin. The hybrid approach is sometimes used in situations where there is a significant difference in the growth prospects of the SpinCo or ParentCo. (i.e., ParentCo is expected to have modest price appreciation potential and SpinCo has strong growth prospects). And it is sometimes the case that different treatments may apply to employees within one entity. For example, if the ParentCo hires a senior executive for SpinCo from outside the company, prior to the spin, their awards may convert using the Employee approach if they have minimal service at ParentCo, yet the Shareholder approach may be used for other employees.

For outstanding long-term performance share or unit/cash plans (typically with three-year performance cycles), practice is mixed, and the conversion approach used will depend on the length of time remaining in the outstanding award cycle, the performance measures used, whether a new program is put in place in SpinCo, and the type of SpinCo company structure. In many cases, ParentCo prorates outstanding LTI awards held by employees of SpinCo to reflect their time as an employee of ParentCo. The prorated awards held by SpinCo employees are then paid out based on the original performance criteria at the time payments are made to ongoing employees of ParentCo. Once employees have transferred to SpinCo, the remaining stub periods of each outstanding award may be paid out at the target award amount, or, in cases where the Committee of SpinCo wants to preserve a performance-based focus, they may establish new performance goals based on operational or stock performance of SpinCo. There are challenges associated with setting goals for these ‘interim’ performance periods, yet many companies will do so.

Retirement Programs. Agreement on the treatment of retirement programs, non-qualified deferred compensation (“NQDC”) plans and other benefits is a critical administrative decision. If ParentCo has a defined benefit plan, it must determine whether to transfer assets and liabilities of the pension associated with SpinCo employees to SpinCo. A decision on whether any applicable grandfathering of frozen plans/plan benefits will continue is also required. Non-qualified benefit programs are often only partially funded, or unfunded, and the amounts can be significant. Typically, employee accounts in any NQDC plan of ParentCo are transferred to a SpinCo plan for employees of SpinCo. Alternatively, SpinCo could receive a payout of the NQDC applicable balances. Plan provisions will dictate the course of action. Note that distributions in connection with a spin-off are generally not compliant with Section 409A of IRC, since a spin-off is not a separation of service for employees under 409A.

Health and Welfare Benefits. Generally, SpinCo is responsible for setting up new health and welfare programs and both ParentCo and SpinCo are responsible for claims incurred against the respective plans post-spin. Certain programs such as retiree medical, however, may require a determination of how to allocate liabilities to SpinCo (e.g., for current terminated employees, or just future retirees). Decisions on allocating liabilities related to LTD payments, accrued vacation, COBRA, workers’ compensation, etc. may also need to be made depending on the programs of ParentCo.

Severance and Change in Control (“CIC) Benefits. A spin-off could trigger a CIC depending on the provisions of ParentCo’s various plans. While many benefits arising from a CIC are only paid after a “double trigger” (i.e., they are only paid or vested if a termination of employment occurs in connection with the CIC), certain benefits may be accelerated or payments may be triggered immediately. As a result, severance payments could become due to employees transferring to SpinCo. The companies need to determine if any severance obligations apply when employees transfer to SpinCo and who bears the responsibility for such obligations. Note however, that in many transactions, outstanding awards are assumed by SpinCo, in which case, payments would not be accelerated, nor would any benefits be distributed.

3. SpinCo Going Forward Compensation

Developing a going forward compensation program for the SpinCo is a critical process that often evolves over time. While the default approach may initially be to maintain compensation programs similar to those of the parent company, there may be a compelling case to make fundamental changes to the compensation program to address differences between the SpinCo and the Parent. However, depending on the time-frame for completion of the spin-off and the corporate governance structure, the timing of any such changes may be delayed.

Corporate governance of a spin-off can vary and we have seen each of the following approaches used:

- SpinCo Board of Directors is led by ParentCo executives through time of spin-off until ParentCo no longer has majority stake

- SpinCo has Independent Board members appointed prior to spin-off; decisions on compensation for SpinCo may be subject to Parent Company Compensation Committee approval

- ParentCo Compensation Committee reviews and approves programs for SpinCo

Prior to a planned spin-off there is typically a designated subcommittee of the Parent company board that begins planning and making decisions related to the SpinCo’s compensation program. A Lead Director may be appointed to oversee this planning process on behalf of the new Board, working with the company’s HR or designated SpinCo CEO. Prior to the spin-off, coordinated efforts to recruit new directors, develop a compensation committee charter and a Board calendar, etc. are required.

In a one-stage spin-off, where all shares of the SpinCo are distributed to ParentCo shareholders at the time of the spin-off, the involvement of ParentCo executives and Board members in SpinCo corporate governance will cease at the time of the spin-off. In other cases, where the SpinCo is distributed in stages (e.g., partial IPO to public shareholders followed by a completion of the spin-off or incremental sale of shares in the SpinCo to the public), the parent company Board or parent company executives may continue to serve as Board members of the SpinCo up until the time that the parent company has fully distributed its interest in SpinCo.

When ParentCo Board members or executives are involved in the compensation design, they are more likely to fall back on maintaining a compensation approach that is consistent with that of the parent. They may continue to view the SpinCo as akin to a subsidiary. In these cases, the SpinCo’s compensation program may evolve from the timing of the initial spin-off through the year following the parent company fully divesting its interests in the SpinCo.

Pay Philosophy and Target Pay Levels

For the SpinCo, there is typically pre-planning around the desired compensation philosophy, including a defined market or peer group for pay and performance benchmarking. This peer group should be size and industry specific, reflective of the operating characteristics of SpinCo and may or may not include similar peers to ParentCo’s peers.

There is often extensive benchmarking conducted before the spin-off to determine competitive pay levels for executive positions at SpinCo, assuming new position roles/responsibilities as part of a standalone entity (vs. part of a business unit, prior to the spin-off). It is often the case that benchmarking for SpinCo as a standalone entity will support an increase in pay for executive positions. For example, the top finance executive of a subsidiary is a very different role than CFO of a stand-alone public company. Some adjustments to base salaries and bonus opportunities may be made prior to and/or near the spin date, but should be made within the context of an overall compensation framework to the extent possible. The desired pay mix needs to be determined, with the appropriate emphasis on long-term (equity) incentives to ensure equity ownership build up and alignment with shareholders.

Annual Incentive Program

As with any company, the ongoing bonus program is designed so that funding is based on an appropriate mix of corporate, business unit and/or individual performance. The mix depends on the company’s emphasis on line of sight unit results or overall corporate team results. Performance metrics, whether top line, bottom line, or return based, should appropriately support the company’s strategy. Some investors may initially focus on EBIT/EBITDA or cash flow, yet ultimately determine that a balanced mix of metrics is desirable.

It is worth noting that for both short and long-term incentives, based on the tax code rules (IRC Sec. 162(m), the “performance based compensation” tax exemption for select executive officers), if a company gets an annual and long-term incentive plan approved prior to the Spin by the ParentCo board, and discloses such plan documents in any S1 filing, the company is exempt from IRC Section 162(m) rules for one year. Reapproval of such plan(s) by SpinCo shareholders is required prior to Sec. 162(m) transition relief expiring, and is also required under applicable stock exchange rules. Most companies, however, will still construct their plans to conform with “performance based compensation” rules and best in class industry/market practices.

Long-term Incentives

Key objectives of the Long-term Incentive (“LTI”) program for the SpinCo are to build executive/ employee stock ownership and to create excitement, engagement and alignment with shareholder value creation.

An important first step is to determine an overall equity pool to reserve for equity grants at the SpinCo, i.e., the amount of public stock outstanding that will be shared with employees as part of the compensation program. (This amount is generally under 10% of CSO, once initial IPO, has occurred and/or upon completion of the full spin; industry norms should dictate). At the initial IPO, or at full spin-off, it is common to grant a front loaded equity award to ‘jump start’ employee ownership in the new company. Some companies make a broad-based award to employees deeper in the organization, or beyond the executive group. Stock options and restricted stock are used for this type of grant, yet use of options (vs. full value awards) should be balanced with participation, share usage and cost considerations.

The core LTI framework for SpinCo should be designed to accomplish multiple objectives. Emphasis on equity programs helps to build shareholder alignment. Stock-based performance programs are strongly recommended. Not only do they reflect prevalent practice, but they are viewed favorably by large shareholders. Performance-based equity will also serve as a tool for the new leadership team to promote a focus on specific longer term performance results.

Like any LTI program, balance is important. While some specific industries may use more restricted stock than others (e.g., energy companies), most restricted stock is granted at lower levels in the organization, or for special retention/recognition grants. As a new entity, any new design presents an opportunity to assess long term performance goals related to business strategy and those being communicated to the marketplace. Such goals should likely be incorporated into the LTI program.

Vesting, form of payout and termination provisions are also important. The spin-off event is an opportunity for the new company to re-evaluate ParentCo practices. For example, SpinCo may choose to implement somewhat more stringent award termination provisions to support longer term employment of employees. To further align with best practice, companies should include CIC provisions that provide for outstanding award vesting only upon both completion of a CIC and termination of employment for good reason (i.e., a “double trigger”).

Severance provisions should be established as part of a formal severance (CIC/non-CIC) program or through severance agreements, or less common, as part of an employment agreement. These programs should be implemented after careful consideration of potential costs and benefits to the participant and to the company. Recognize that severance benefits are a sensitive issue for many investors. Tax gross-ups for any 280(g) CIC tax liabilities are no longer common and should not be included. Non-compete and non-solicitation provisions should be put in place for the new entity, as standalone policies or as part of LTI award agreements.

Governance Practices

Certain good governance practices that are commonly in place should be implemented, as they are in the best interests of SpinCo and shareholders and have come to be expected.

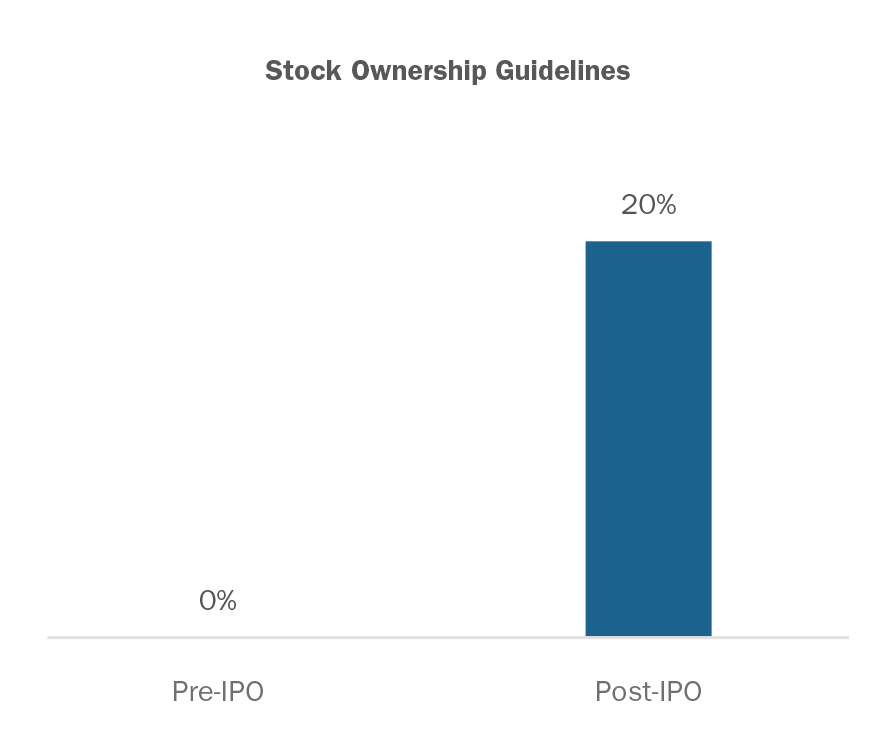

Stock Ownership guidelines are now very mainstream and expected by shareholders. They should apply to the newly formed executive group. In SpinCo, it may take some time to ramp up ownership in SpinCo stock, particularly if outstanding ParentCo equity awards were converted at spin using the shareholder approach. Keep in mind there should be a phase-in period before executives are held accountable and a ‘soft’ penalty my make sense, to help facilitate ownership, such as a required holding of 50% of net shares (vested or settled), until the guideline is met.

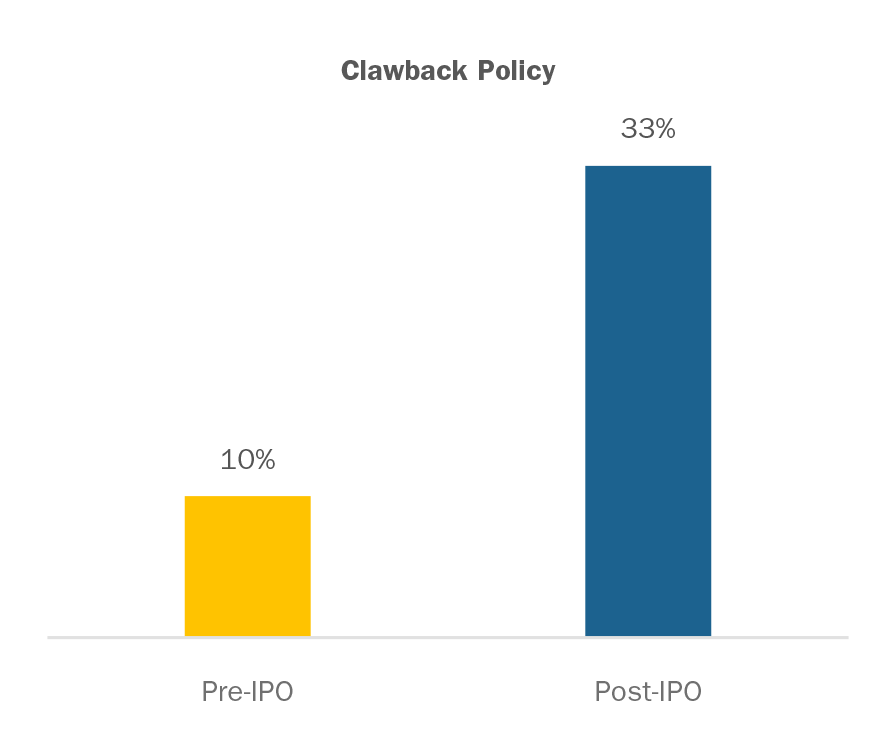

A Clawback Policy for any awards that were based on results impacted by an accounting restatement is a matter of good governance. A majority of companies today have one, with the ability for discretionary recoupment in the case of fraud or earnings restatement. Note that potential Dodd-Frank rules may mandate a “no fault” policy if finalized.

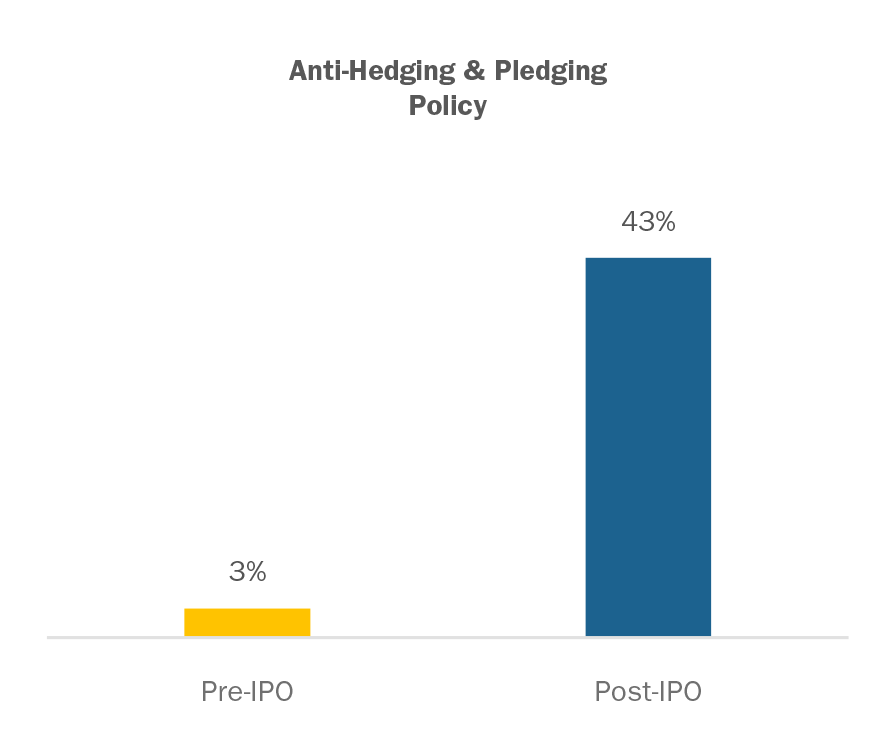

An Anti-Hedging Policy should be in place that prohibits executives from entering into any hedging transactions related to the company’s stock or trading any instrument related to the future price of the stock.

If Dodd-Frank rules are finalized as currently expected, companies may need to modify these provisions to comply with final rules, but on their own merit, these provisions should be put in place as a baseline.

Directors Compensation. The outside directors’ compensation program of SpinCo should ultimately reflect appropriate market norms for companies of similar size and industry, in terms of the amount of pay provided, the cash/equity mix, and overall structure of board and committee service pay. The design should consider the duties required of directors, as well as the company’s executive compensation philosophy. Initially however, the structure of SpinCo’s program will often resemble the ParentCo program.

The directors equity plan, if separate, follows the same rules as executive equity plans. The ParentCo board typically approves the SpinCo plan prior to the spin-off. Shareholders of SpinCo must reapprove the plan prior to IRC Sec. 162(m) transition relief running out, and also to comply with stock exchange listing requirements.

If any directors work on SpinCo activities prior to the spin-off, special equity compensation may be awarded, or pro-rated. If board leadership includes a non-executive chair or lead director, compensation will need to reflect the expected role, responsibilities and time commitment expected at that time.

4. Modification to ParentCo Compensation Programs Post-Spin

After the spin transaction, it is a good time for the remaining ParentCo to review its own compensation programs to ensure that they reflect the company’s new size and business focus. While not inclusive, the following program components may require review and/or potential modification:

Compensation Philosophy and Competitive Market. The company should assess who the appropriate peer companies are in terms of size, business mix, customers, geographic footprint, domestic vs international business, etc. It may be that the company maintains a market median pay philosophy, but that market position means something different now. If the company’s size is significantly smaller than before, pay levels will need to be monitored for alignment with the newly defined market over time.

Annual Incentive Program. The company’s annual incentive plan, in particular, may need revision so that the performance metrics reflect key drivers of the remaining entity and adjustments to the plan should reflect the new adjustments to the plan should reflect the new organization structure as it relates to any Business Unit or Division performance components. If the remaining business has slower growth prospects and lower margins, for example, the performance metrics may need to be redefined and the weightings reallocated. It may also be the case that there is more of a role for strategic goals as ParentCo also embarks on a new business strategy.

Long-term Incentive Plans. The company should reassess the role of various LTI vehicles at ParentCo. For example, in a low growth business, stock options are not the most effective long term incentive and the company may be better served by increasing the role of a three year LTIP. Conversely, the company may want to instill renewed enthusiasm around the ParentCo’s long term stock performance and growth potential. It may be an appropriate time to emphasize the role of equity. It is also a good time to reassess equity award participation as it relates to overall cost and/or share utilization, both domestically and internationally.

From a more technical standpoint, the Parent should review its current equity plans and share reserve, in light of the recapitalization. A spin-off event itself may not necessarily require revisions to plan documents, but it is an appropriate time to review documents to ensure that appropriate terms and provisions are included. It is also a good time to review compliance with IRC Section 162(m) and 409A.

The compensation related programs and provisions that need to be addressed and acted upon in a spin-off are comprehensive. It is important to the ongoing entities that both ParentCo and SpinCo business objectives are supported by appropriate pay design. At the same time, employee perspectives need to be considered as these transactions can present uncertainty. Planning should begin well in advance of any potential or planned transaction. A cross-functional team from HR, legal, finance and possibly outside advisors, should oversee the necessary action steps. This report can be used to help guide the process and compensation decisions that an organization will need to consider in a spin-off.

1 Source: www.spinoffresearch.com

The transition from a private company to a public company is an exciting time for most organizations. For employees, moving from private to public status provides the first opportunity to potentially gain liquidity from equity-based. For venture capital or private equity investors, it typically represents the first opportunity to realize gains from their investment and risk-taking. However, becoming a public company creates new disclosure requirements and opens up compensation programs to scrutiny from a new group of public shareholders and shareholder advisory firms.

Not all newly public companies are the same. In this white paper, we will speak generally about newly public companies, but also address differences that may apply across categories. The categories we most typically see are the following:

- Recent Start-ups: Companies that have been funded primarily by venture capital backers and are in early stages of development

- Often these companies are in the biotech or internet/technology industry and some, in particular in biotech, may be pre-revenue and likely pre-profit when they go public.

- Companies in this category are usually emerging growth companies (revenue less than $1 billion at IPO) under the JOBS act, subject to less stringent disclosure requirements and exempt from Say on Pay votes for up to five years following IPO

- Private Equity Portfolio Companies: More mature businesses that may have been taken private to improve operating performance

- Typically are profitable businesses and trade based on multiples of earnings or EBITDA

- May or may not be “emerging growth companies” under the JOBS act

- Private equity owners may continue to maintain a majority interest following IPO

- Spin-off Companies: Business units of a publicly traded company that become public through a spin-off event

- Spin-off may occur in one stage, an initial IPO and then a spin-off of remaining shares, or a multi-stage sell-down

- In most cases, the spin-offs are mature companies that are viewed as being able to generate more value on their own through greater strategic focus than as part of the parent company

Establishing Public Company Compensation Processes

As a public company, there is an increased requirement for processes governing the company’s compensation decisions. All public companies (other than those controlled by a 50% or greater shareholder) need to have a Compensation Committee of two or more independent directors. The Compensation Committee needs to have a Charter that lays out the responsibilities of the Committee, including its responsibility for overseeing the pay of the CEO and the other executive officers of the company.

In practice, there is a lot of work to set-up a functioning Compensation Committee. Key steps to get a Committee up and running include the following:

- Identify Members: The Board needs to determine which directors have the capabilities and experience to effectively serve on the Compensation Committee;

- Appoint a Chair: The Board needs to identify a Chair for the Committee who can ensure that the Committee operates effectively and meets its responsibilities under the Charter;

- Draft Charter: Company’s counsel needs to draft a Charter outlining the Committee’s responsibilities in compliance with the listing standards of its respective exchange and addresses the expectations of the Board for the Committee;

- Establish Committee Calendar: Human resources needs to work with the Committee Chair to develop a calendar of activities for the year (including the timing and number of Committee meetings) and cross-reference with the Charter to ensure that all responsibilities are addressed;

- Assess Need for External Advisor: The Committee needs to assess whether or not they need an advisor; if they elect to use an advisor, they need to conduct a selection process and assess the independence of the advisor;

- Develop Committee Meeting Process: Establish protocols for the companies interaction with the Committee and preparation for meetings; best practices include the following:

- Provide Committee Chair with a draft agenda for the meeting at least one month in advance of the meeting;

- Review draft materials with the Committee Chair (and Committee advisor) at least 1-2 weeks in advance of the meeting;

- Make materials available to Committee members one week in advance of the meeting;

- Ensure that at least 2 meetings are provided for major decisions; one meeting to review and second meeting to approve; and

- Follow-up with Committee Chair following Executive Session to confirm decisions made in the meeting.

Many companies adopt some of the above practices in advance of going public and this tends to make the transition easier. We find that new Committees have some room to learn as they go; however, the fundamentals of the process should be in place upon going public.

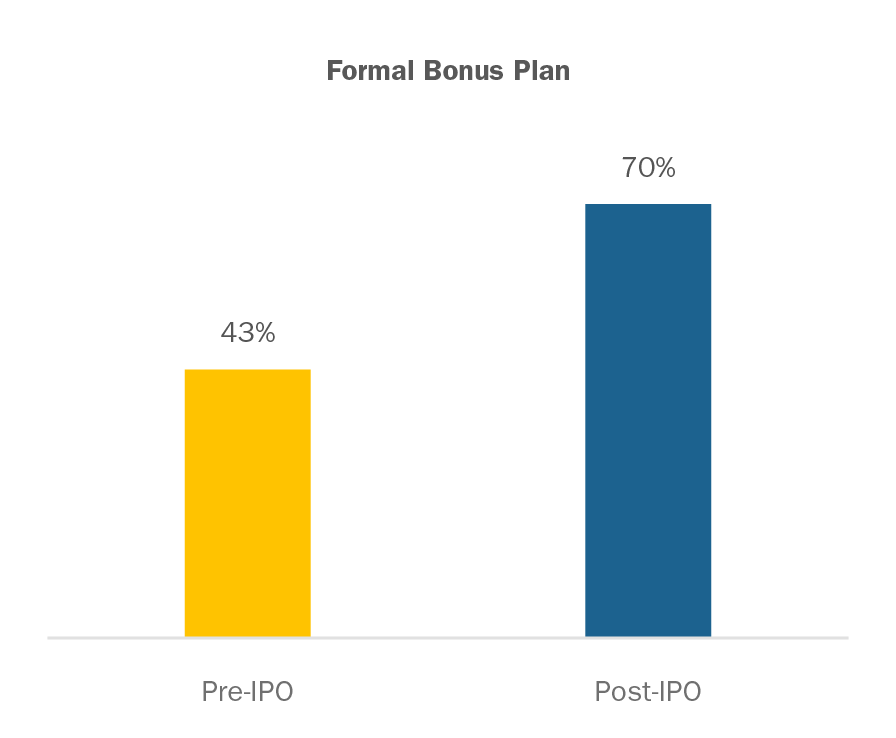

Post-IPO Compensation